Editor’s note: This commentary is an exclusive to redefinED from Sean-Michael Pigeon, who recently graduated with a B.A. in political science from Yale University. He works as a journalism mentor at a magnet school in New Haven, Conn. His writing has appeared in USA Today, the Washington Examiner and the Washington Times.

The number of magnet schools has grown steadily over the last two decades, further increasing the control parents have over their child’s education. Many argue the most important point of magnet schools is that they allow parents to choose where and how their child is taught.

But in response to recent critiques, selective magnet schools have begun restricting enrollment by implementing zip code quotas. Not only does this cut against the goal of magnet schools; its focus is misguided.

One of the critiques levied at magnet school is that magnet schools are not diverse enough, either racially or economically. This is an important criticism for magnet schools to address, given that they were implemented in part to help desegregate school systems.

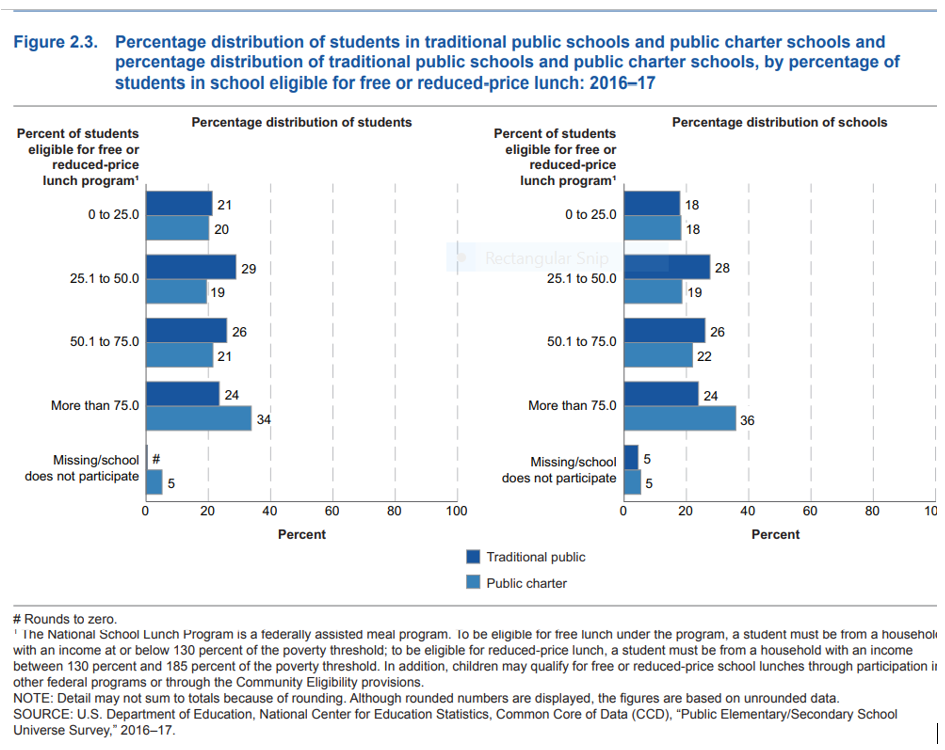

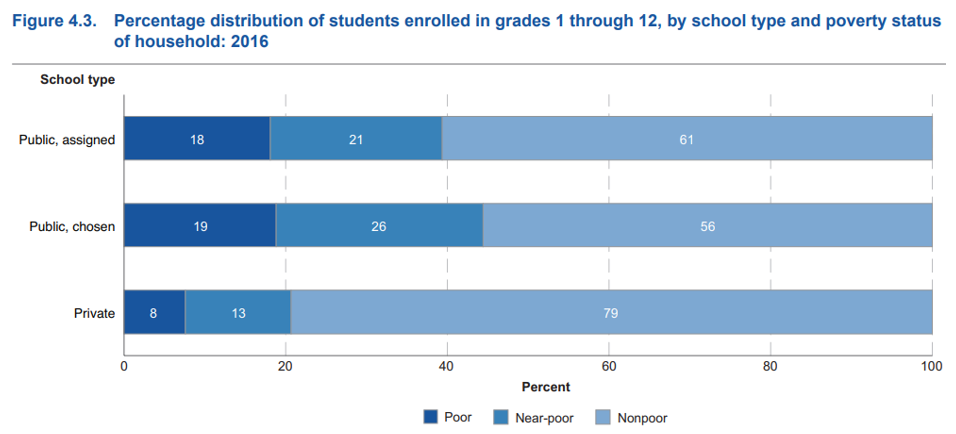

Yet the most recent evidence suggests magnet schools incorporate more ethnic minorities than traditional public schools or private schools. A 2019 U.S. Department of Education report found that a higher percentage of public charter school students were Black or Hispanic (See Figure 2.3.) In this case, “public charter” includes both magnet schools and charter schools. The report also found that “chosen public schools” had a higher percentage of poor and “near-poor” students than either traditional public schools or private ones (Figure 4.3).

This means there is no evidence that magnet schools, on average, do a better job of integrating different racial and socio-economic communities than either assigned public schools or private schools. Nevertheless, certain highly selective magnet schools have come under fire for using test scores to determine whether a student is admitted.

This means there is no evidence that magnet schools, on average, do a better job of integrating different racial and socio-economic communities than either assigned public schools or private schools. Nevertheless, certain highly selective magnet schools have come under fire for using test scores to determine whether a student is admitted.

Some parents argue that changing magnet schools’ admissions to a lottery system is long overdue. It is true that the student body of Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology (the top high school in the nation, and a magnet school), skews disproportionately Asian. However, there are many minority-majority magnet schools that also are high-performing magnets.

For example, Irma Lerma Rangel Young Women’s Leadership School (ranked No. 15 in the nation and No. 2 in Texas) has a student body that is overwhelmingly Hispanic, at 79%. If a lottery were implemented for Irma Lerma’s admission based on Dallas County, which is majority white, the ethnic makeup of the student body would change significantly.

Equity advocates should be wary that their efforts do not undermine the ability of magnet schools like Thomas Jefferson and Irma Lerma to nurture a school environment that has proved effective. Just because a school has a minority-majority student population, it doesn’t necessary follow that its admissions process needs dismantling.

We do not need to imagine what instituting racial quotas would do for magnet school admissions. Take, for example, University High School of Science and Engineering, a magnet school in Hartford, Connecticut. To promote desegregation and racial equality, the school is required to limit Black and Hispanic enrollment to under 75%. Connecticut courts have upheld the policy that schools like University High cannot decrease the percentage of white students required for diversity, causing widespread frustration.

One city mom was devastated that her son could not attend University High. “I was told,” she says, “‘Well, white kids from the suburbs have to apply for him to get in.’”

A recent lawsuit lobbied by Virginia parents that argued the new practices set up by Thomas Jefferson High School purposefully discriminated against Asian Americans was allowed to proceed. While those parents await the outcome, we must ask why parents must appeal to the courts to send their children to a school they would otherwise be qualified to attend.

Chosen public schools, like magnets, have proved effective in achieving learning goals while serving more minority and low-income students than any other form of schooling. Throughout the difficult 2020-21 academic year, many magnet schools led the way in transitioning to virtual learning. Other magnet schools helped students deal with mental health problems by crafting innovative solutions to isolation.

Barring high-performing and/or willing students from attending a magnet school simply because of where they live or their ethnicity is antithetical to the very point of such schools. It would be foolish to sacrifice the success of magnet schools across the country to target a problem not in sight.