Debbie Veney already had earned a journalism degree from Howard University when the nation’s first public charter school, City Academy Charter School in St. Paul, Minnesota, opened its doors nearly 30 years ago. She enjoyed the benefits of education choice by attending a Catholic school.

“It was small and very student focused,” recalled Veney, who grew up in Washington, D.C. “It was a predominantly Black school, and it was a really interesting experience for me to be in a private school setting that was culturally affirming and academically rigorous.”

Today, Veney is senior vice president of communications for the National Alliance of Public Charter Schools, the largest nonprofit advocacy group specifically dedicated to supporting charter schools, which are funded with public dollars but are privately managed. Unlike private schools, charter schools do not charge tuition.

Based in the nation’s capital, the alliance works to educate lawmakers and thought leaders about how charter schools can meet the needs of the communities they serve by providing families with public school options.

It also advocates for legislation that will advance the charter school movement. As host of the annual National Charter Schools Conference, the alliance brings together educators, leaders, lawyers, researchers and policy experts.

Veney was the mastermind behind the organization’s recent study that showed charter schools experienced their greatest enrollment boost in six years during the 2020-21 school year, even as traditional district schools saw declines.

She had seen local stories in January about the growth of charter schools and shrinkage in district schools in different parts of the country and “was curious about whether there was really a significant pattern here or whether these were one-offs.”

The study, which covered 42 states, showed charter schools gained nearly 240,000 students – a 7% increase – from 2019-20 to 2020-21. Other public schools, including district-run schools, lost more than 1.4 million students, a 3% loss, during the same period.

“We became a very popular option for a lot of parents, and what was really interesting to me was that you could see this pattern of where there was any capacity at all, parents maximized that opportunity and grabbed as many seats as they could.”

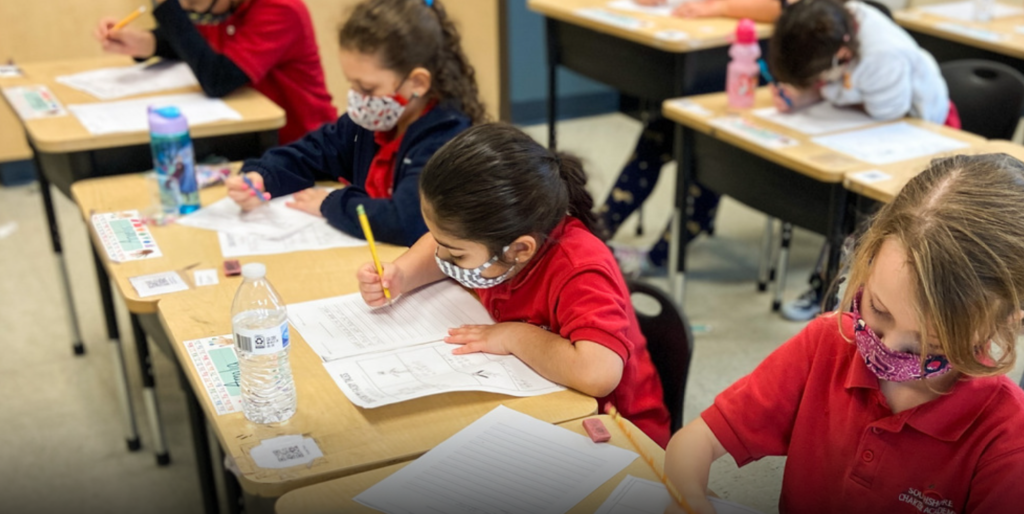

As district campuses in many areas stayed shuttered, many charters remained open for in-person learning, prompting parents who may have been dissatisfied with their district’s remote learning program the prior spring to seek alternatives.

Though Florida kept its district campuses open, the trend of charter school growth over district schools still held.

Veney speculated that could have been because parents got “an up close and personal” look at what districts were teaching during the spring 2020 quarantine and wanted something different.

“Even with schools that didn’t close, it was as if there was this window of time where people rethought a lot of stuff,” she said. “I figured out some things that I would have never figured out if there hadn’t been a pandemic.

“I think there was a lot of word of mouth that went on. I saw parents who left ‘A’ rated schools because they wanted a different type of experience.”

Veney said the study turned up a few surprises, namely that several states reported decreases in charter school enrollment, albeit extremely modest, such 9 fewer children in Iowa and 22 fewer in Wyoming.

The largest decline was in Illinois, where charters lost 702 students, a decrease of 1.1 % over the previous year. But traditional district schools in that state lost 66,806 students, a decline of more than 3.5%.

“Some of it may have simply been a factor of students (who) graduated,” she said. “And a lot of parents didn’t enroll their children in kindergarten.”

She also pointed out that the Census reported an explosion in homeschooling, which parents who may have been unemployed or working from home decided to try.

Veney, who counts among the most significant trends she has witnessed the rise of national networks that are able deliver “amazing” results, said she foresees a new wave of parental involvement even as the pandemic panic fades into memory.

“Looking ahead, I see parents are really going to be more vocal about what they want for their kids,” she said. “I’m seeing more parents being more directive now, realizing they have the voice to do that.”

She also predicts more grassroots involvement in the charter movement as opposed to operators from distant places starting schools.

“I think we are going to see a lot more people who are from that community using their voices and becoming advocates,” she said. “I don’t think we can go back to pre-pandemic times.”