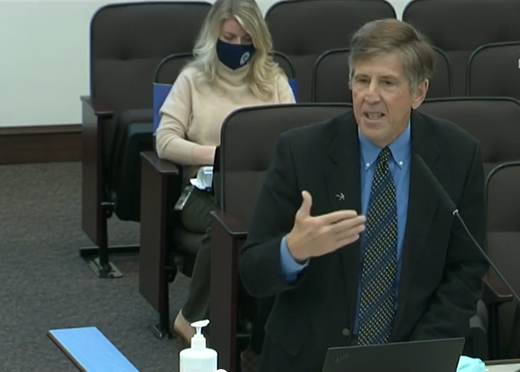

Editor’s note: This commentary from Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill is a transcript of a podcast the reimaginED team recorded earlier this month. You can listen to the podcast here.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill is a transcript of a podcast the reimaginED team recorded earlier this month. You can listen to the podcast here.

Q: Let’s start with your thesis. What main points do you think are important about teacher unions?

Tuthill: Unions have a symbiotic relationship with the industries within which they operate. A union’s business model is a function of how its industry is organized. The business model of a trade union representing carpenters and plumbers will reflect how the construction business is organized. A union representing home health care workers will reflect how the home health care industry is organized. And a union representing district schoolteachers will reflect how school districts are organized.

When the way an industry conducts business changes, the union’s business model must also change. Unions representing taxi drivers and retail mall workers are changing as ride-sharing services expand and much of retail shopping moves online.

Public education is in the early stages of a transition that is as impactful as how ride-sharing and online retail are transforming their respective industries. Public education is becoming more decentralized and public education services are increasingly being delivered outside of school districts.

One-size-fits-all education services are being replaced by customized services. Control of public education funds is transitioning from school districts to families. Teacher unions need to start transforming their business model to adjust to these industry-wide changes.

Q: What is your history with teacher unions and the labor movement?

Tuthill: I grew up in a blue-collar union household. Dad was a member of the firefighters’ union and Mom was a United Auto Workers member. Mom went on strike a few times and I was in middle school during the 1968 statewide teacher strike in Florida.

I became a union organizer in the spring of 1978 when I was elected president of the Graduate Student Union in Florida. We were affiliated with the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the AFL-CIO. We were also part of the United Faculty of Florida (UFF), which is the statewide faculty union representing college and university professors. I served on the UFF executive committee and was active in the AFT and the AFL-CIO.

In 1981, the AFL-CIO president asked me to serve on the organizing committee for the Solidarity Day march in Washington, D.C. That work lasted several months, involved hundreds of AFL-CIO unions, and about 500,000 marchers.

In 1984, I started teaching high school in St. Petersburg and became an active leader in our teachers’ union, the Pinellas Classroom Teachers Association (PCTA). I was PCTA vice president from 1988-91 and president from 1991-95. I also served on the board of directors of the statewide teachers’ union and did a lot of work nationally, and some work internationally, for the National Education Association (NEA), which is the country’s largest teachers union.

In 1995, I was a founding member of AFT/NEA sponsored Teacher Union Reform Network (TURN). I worked with TURN through 2001. From 2001 to 2003 I ran a union-sponsored organization that trained teachers and teacher union leaders.

Q: You toured the country in the early 1990s promoting a concept called new unionism. What was new unionism?

Tuthill: New unionism proposed a new mission for teacher unions. Instead of unions using their collective power to protect teachers from dysfunctional management systems, new unionisms advocated using this power to improve those systems.

The good people leading and working in school districts are well intentioned. But school districts still use a late-1800s industrial model of centralized, command and control management, which may be good for manufacturing Model T Fords but is an ineffective and inefficient way to manage public education. As a union organizer, I sold teachers protection from the many threats they faced working in these old industrial management systems.

Selling protection only works if people feel threatened, which is why teacher unions work to preserve these 19th century management systems while simultaneously selling teachers protection from those systems. Ironically, teachers are paying unions to perpetuate a system that threatens them, and for protection against these threats. The current teacher union business model is a protection racket. New unionism sought to change that.

Q: Why did teacher unions reject new unionism?

Tuthill: My friend Bob Chase was on the NEA Executive Committee. We spent several years discussing new unionism and Bob decided to make it a centerpiece of his 1996 campaign for NEA president. Bob got elected, but new unionism died early in his first term.

Protecting teachers from bad management is a very profitable business model. But more importantly, public education has been organized like an industrial assembly line since the 1800s. That model is deeply ingrained in local, state, and national policies, practices, and norms, and fiercely resistant to change.

Teacher unions will not improve until the larger public education ecosystem improves. Teacher unions are a subset of that ecosystem, and their business model derives from it.

Q: You assert that education choice is a necessary condition for improving public education and teacher unionism. Elaborate on this argument.

Tuthill: Public education is an overregulated, poorly performing market. The quality of our markets largely determines our standard of living. Imagine if the government owned all the housing in the United States and told people where they had to live.

Imagine if the government owned all the grocery stores and assigned people to grocery stores by ZIP code and assigned them the food they had to eat each day. In these scenarios the housing and food markets would function badly. There would be little innovation in housing or nutrition and people would rebel.

No one would tolerate the government dictating their housing and daily nutrition, and yet that’s how public education operates. We assign children to government-owned schools. We tell them what curriculum they will consume each day. And we now have about 150 years of evidence showing that doesn’t work for most students.

Despite all the evidence demonstrating that poorly functioning markets are bad, we continue insisting that public education be a poorly performing market. Giving families control over their child’s public education dollars is a necessary step toward creating a more effective and efficient public education market, which is why I support education choice. Education choice is a necessary condition for improving the public education market.

Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) contribute to a higher-performing public education market because they give families control over their child’s public education funds and provide them with the flexibility to purchase education services and products customized to each student’s needs.

As more families use ESAs, educators will have more opportunities to innovate and create more diverse education options they will own and manage. These changes will create new business opportunities for teacher unions.

Unions could help teachers create and manage their own education businesses, including micro-schools, virtual schools, home-school cooperatives, tutoring services, afterschool, weekend and summer programs, and traditional brick-and-mortar private and charter schools.

Teacher unions could help teachers access financing for physical infrastructure needs and provide administrative services such as bookkeeping, professional development, accounting/payroll, human resources, IT support, purchasing cooperatives, and employee leasing. (Some teachers may want to be employed by their union and contract with schools or other education providers on a part-time or full-time basis.)

Most teachers today must work in school districts because that’s where the jobs are. Freeing them to work for themselves or other teachers will allow them to have the professional status they have long been denied.

If lawyers can have lawyer offices, doctors can have doctor offices, and accountants can have accounting offices, why can’t teachers have similar professional opportunities? Why can’t teachers own public education businesses, and why can’t their union help them create and maintain these businesses?

For the foreseeable future, most teachers will continue working in district-owned schools. For these teachers, unions can continue offering their traditional protection, advocacy, and financial services, including legal protection, insurance, political advocacy, credit cards, and bargaining for salary, benefits, and working conditions.

Teacher unions do have opportunities to innovate within their current blue-collar union model. For example, professional sports unions integrate employee empowerment into their collective bargaining by negotiating minimum salaries and creating a well-regulated market within which individual employees may receive salaries well beyond the minimums. Many district teachers today would embrace the opportunity to be paid their true market value.

Q: Why won’t this version of new unionism fail like the last version?

Tuthill: In the early 1990s the public education ecosystem was not transforming like it is today. Currently, over half of Florida’s PreK-12 students are not attending their assigned district school. As more families assume greater control of their child’s public education dollars, teachers will increasingly leave school districts to take advantage of the opportunities created by this decentralization of public education spending. This expanding number of students being educated by teachers outside of school districts will eventually force teacher unions to begin selling services to these non-district employed teachers.

The pressures that led the NEA to become an industrial union provide a roadmap for how this next chapter of teacher unionism may unfold. The NEA was founded in 1857 and for over 100 years considered itself a professional association and not an industrial labor union. The AFT was founded in 1916 as a labor union for teachers. The first teacher union labor contract was ratified in 1962.

This contract launched the modern teacher union movement. Teachers in urban areas across the country began organizing themselves into labor unions and bargaining union contracts. AFT started to grow rapidly, and as NEA market share losses accelerated the pressure to turn the NEA into a labor union grew. By the mid-1970s the NEA had transitioned from a professional association to an industrial labor union.

As today’s teacher unions increasingly lose market share to organizations providing services to teachers working outside of school districts, they will start selling services to these non-district teachers in an effort to protect and recoup their market share. The NEA transition occurred over a period of about 20 years. I suspect a 20-year transition will also be needed this time. What I don’t know is when this transition will begin.

Q: Are you still a believer in teacher unions?

Tuthill: Teacher unions are comprised of good people working in bad systems. With the appropriate business model, teacher unions would be an asset in our efforts to create a more effective and efficient public education market.