WILLISTON, Fla. – When Misty Dodd’s daughter Taelyr was in third grade, her teachers told Dodd that “Tae” needed to be in a school with more rigor. Tae, now 13, was enrolled in the neighborhood school’s gifted program. But she was making straight A’s without breaking a sweat, and so bored, she was racking up demerits for being too chatty.

The teachers suggested a school in Gainesville. But for Dodd, it wasn’t an option. With traffic, it was 45 minutes to an hour from their home in Williston, a town of 2,700 surrounded by pine forest and pasture. And Dodd, a single mom, works 70 hours a week to make ends meet.

“I was embarrassed and frustrated,” said Dodd, who still cries at the recollection five years later. “I was thinking my daughter is going to get lost. What if she loses interest because it’s not challenging enough?”

“I was thinking, ‘I’m going to let her down,’ ” Dodd continued. “I thought, ‘She’s not going to get the education she deserves.’ ”

Thankfully, the story of Tae and her mom has an almost perfect ending.

Almost.

Dodd found Tracy Kirby, a former public school teacher who started a home-school co-op on a farm full of trains. Kirby is now Tae’s teacher.

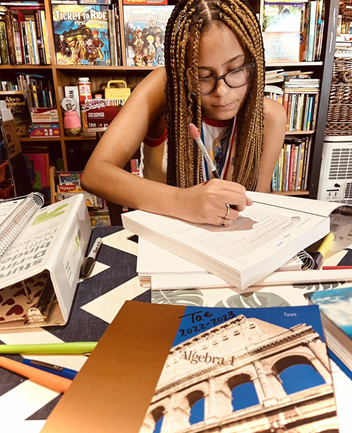

Tae attends the co-op one day a week, then works with Kirby one-on-one, in person, for several hours on another day. Kirby assigns Tae work for the week, and Tae touches base by phone or online as often as necessary.

For Tae and her mom, the arrangement works.

“What Mrs. Kirby does is amazing, and Tae loves it,” Dodd said. “I know I can trust Mrs. Kirby. There’s a 200 percent difference between now and before.”

“The main difference now is, I’m challenged,” Tae said. “Academically, there’s always something for me to do. And if there’s something else I want to do, I can ask, and Ms. Tracy can work it into the curriculum.”

By age, Tae is an eighth grader. But in most of her subjects, she’s performing at a ninth grade level or higher.

The only downside – and it’s a serious one – is cost.

Dodd works two jobs – one as a clerk at the Florida Department of Motor Vehicles; the other as a waitress. It’s not easy paying for Tae’s education. Kirby doesn’t charge for the co-op programming, but there is a fee for the 1-on-1 tutoring. Dodd must also pay for books, a laptop, a printer, and other supplies.

A state-funded education savings account (ESA) that would pay for those expenses, and other learning supplements for Tae, would be “incredible,” Dodd said. “I work two jobs in part to pay for that. A scholarship would be a blessing.”

Florida does have an ESA. It’s popular and successful. But it’s limited to students with certain special needs. Tae is not eligible.

Florida also has the most expansive private school choice programs in the nation. But unlike ESAs, which can be used for a variety of services and providers, traditional school choice scholarships are limited to private school tuition. Dodd could qualify for a traditional scholarship, where eligibility is determined by family income. But it wouldn’t do Tae any good.

(Both the ESA and the income-based scholarships are administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

Dodd said she never considered private school for Tae because Kirby’s approach is so good.

Kirby tailors the curriculum to fit Tae’s needs and interests. Tae takes many of her core academic classes through Florida Virtual School. She accesses electives through other online platforms (everything from typing to logic to archaeology). Kirby coordinates all of it, then tops it off with her own guidance and instruction and an emphasis on project-based learning.

For example, Tae is passionate about writing. So Kirby frequently gives her writing assignments, from essays to short stories. One time, Kirby asked Tae to study the past winners of a Florida speech contest. She wanted Tae to learn the techniques behind good speeches and to work on her public speaking skills.

“This propelled her to become an expert and figure out what made dynamic speeches,” Kirby said. “She doesn’t stop until she discovers the why.”

“I continuously find myself in shock over her writing,” Kirby continued. “She has a sharp imagination and adds humor. She can also be serious and argue a point.”

Tae is organized and driven. On her own, she read “The Diary of Anne Frank” in third grade and “The Yearling” in fourth grade. In fifth grade, Kirby gave Tae a thesaurus. She also showed Tae how she took notes in college, and Tae used Kirby’s system as a guide to create her own, better system.

“She’s unlike any student I have seen in all my years of teaching,” Kirby said. “The effort she puts in on her own is remarkable.”

Finances, though, are putting limits on Tae’s pursuits.

Tae is fascinated with forensic science and criminal psychology. Kirby said she’d love to look for STEM kits and online programs that mesh with Tae’s interests, and perhaps enroll Tae part time in a school that specializes in crime scene investigations.

“She’d love it,” Kirby said. “She’d be a little mad scientist.”

But all of that costs money Dodd doesn’t have.

An ESA would change that.

If it’s akin in value to the state’s school choice scholarships, it would cost taxpayers far less than per-pupil spending in Florida district schools. And for students like Tae, the return on investment would be invaluable.

Without Kirby, Dodd said, Tae might have become self-conscious about her intellectual interests and retreated into a shell. “She might have gone backwards,” Dodd said.

Kirby said other students have come to her co-op in that shell, shaped by past schooling experiences. In a different setting, they blossom into self-motivated learners like Tae.

If the state’s scholarships offered more flexibility, more students could access those environments.

For Tae and her mom, it’d be perfect.