Editor’s note: This report from Jonathan Butcher, Will Skillman Fellow in Education, Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, and Jason Bedrick, Research Fellow, Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, concludes that education savings accounts empower parents with the ability to meet every child’s unique education needs and should be available to all school-aged children. It includes a review of changes to education savings account plans around the country, specifically in Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

Editor’s note: This report from Jonathan Butcher, Will Skillman Fellow in Education, Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, and Jason Bedrick, Research Fellow, Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, concludes that education savings accounts empower parents with the ability to meet every child’s unique education needs and should be available to all school-aged children. It includes a review of changes to education savings account plans around the country, specifically in Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

In July 2022, Arizona lawmakers converted the nation’s oldest K–12 education savings account (ESA) policy into the country’s most inclusive learning option: Every child in Arizona can now apply for a private account that empowers families to customize a student’s learning experience according to his or her unique needs.

News Release, “Governor Ducey Signs Most Expansive School Choice Legislation in Recent Memory,” Office of Arizona Governor Doug Ducey, July 7, 2022, https://azgovernor.gov/governor/news/2022/07/governor-ducey-signs-most-expansive-school-choice-legislation-recent-memory (accessed October 12, 2022).

With an ESA, the state deposits a portion of a child’s education spending from the state K–12 formula—the formula used to determine per-student spending in traditional schools—into a private account that parents use to buy education products and services for their children. The accounts are worth approximately $7,000 for mainstream children, with larger amounts awarded to children with special needs.

Families can use an ESA to hire a personal tutor for their child, find an education therapist, pay private school tuition, buy curricula and textbooks, save money from year to year for future expenses, and more. The accounts allow families to choose more than one education product or service; moreover, they provide the versatility parents needed to continue their children’s education during the pandemic when schools were closed to in-person learning.

Jonathan Butcher, “COVID-19 Has Accentuated Value of Education Savings Accounts,” reimaginED, May 12, 2020, https://nextstepsblog.org/2020/05/covid-19-has-accentuated-value-of-education-savings-accounts/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

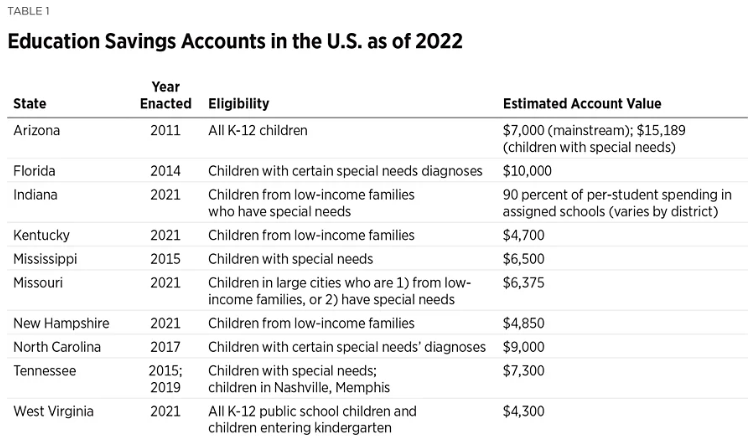

Arizona lawmakers adopted the nation’s first ESAs for children with special needs in 2011, and nine other states (Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia) subsequently created similar ESA opportunities for eligible students. Each state offers accounts to children who meet different criteria.

After the pandemic, as researchers report steep learning losses across grade levels and subjects, the call for quality learning options is especially urgent. Arizona’s new law is remarkable because all K–12 children can participate.

In Florida and Tennessee, for example, children with certain special needs are eligible, while Mississippi and North Carolina’s accounts operate under strict caps on the number of participating students due to either provisions in state law or annual appropriations. In West Virginia, all children attending public schools or entering kindergarten are eligible, making it the second-most inclusive ESA policy behind Arizona’s.

Research conducted by The Heritage Foundation in 2017 helps to explain the eligibility criteria and other account details for the savings accounts in Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Tennessee, but much has changed in the past five years.

Jonathan Butcher, “A Primer on Education Savings Accounts,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 3245, September 15, 2017, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2017-09/BG3245.pdf.

The 2017 report also distinguished between the accounts, which allow families to purchase more than one education product or service at the same time, and school vouchers, which parents can only use to pay private school tuition for their children. The accounts also differ from tax-credit scholarship policies, which provide tax credits to individuals or corporations that make charitable donations to nonprofit organizations that in turn award private school scholarships to eligible students.

Jason Bedrick, “Earning Full Credit: A Toolkit for Designing Tax-Credit Scholarship Policies (2022 Edition),” Pioneer Institute, March 30, 2022, https://pioneerinstitute.org/pioneer-research/earning-full-credit-a-toolkit-for-designing-tax-credit-scholarship-policies-2022-edition/ (accessed October 31, 2022).

In this Backgrounder, we will review the changes to education savings account plans around the country, offer an analysis of the new states with ESA laws, and provide policy recommendations for the future of ESAs.

What’s changed?

Nearly all education savings account plans created since Arizona introduced the concept in 2011 have changed eligibility, funding mechanisms, or other significant provisions:

Arizona. Arizona’s accounts were initially only available to children with special needs but expanded to include children assigned to failing schools and children adopted from the state foster care system in 2012.

Butcher, “A Primer on Education Savings Accounts.”

Lawmakers later expanded student eligibility to include children from active-duty military families and children living on tribal lands, among others. In 2022, Arizona opened eligibility to every K–12 student in the state, some 1.1 million school children.

News release, “Governor Ducey Signs Most Expansive School Choice Legislation in Recent Memory.”

When Governor Doug Ducey (R) signed the expansion, 11,775 Arizona students were using the accounts, and after the application period opened in September 2022, the state department of education received about 22,500 new applications from interested families within two months.

Jason Bedrick and Jonathan Butcher, “Arizona Shows the Nation What Education Freedom Looks Like,” Newsweek, September 14, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/arizona-shows-nation-what-education-freedom-looks-like-opinion-1742145 (accessed October 12, 2022); EdChoice, “Arizona: Empowerment Scholarship Accounts,” https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/arizona-empowerment-scholarship-accounts/ (accessed October 31, 2022); and Christine Accurso, “Arizona’s New ESA School Choice Law Is a Win for Everyone,” The Washington Examiner, September 9, 2022, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/restoring-america/community-family/arizonas-new-esa-school-choice-law-is-a-win-for-everyone (accessed October 12, 2022); Eryka Forquer, “Applications for school vouchers at nearly 22,500 so far, Education Department says,” Arizona Republic, October 7, 2022, https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona-education/2022/10/07/arizona-school-vouchers-nearly-22-500-applications-pour-so-far/8208504001/ (accessed November 3, 2022).

Florida. In 2014, Florida lawmakers enacted the nation’s second education savings accounts, called Gardiner Scholarships. In 2021, state officials adopted a proposal to combine the program with the state’s K–12 private school scholarship program, called Family Empowerment Scholarships, creating the Family Empowerment Scholarships for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA).

Step Up for Students, “Basic Program Facts about the Family Empowerment Scholarship (formerly the Gardiner Scholarship),” https://www.stepupforstudents.org/research-and-reports/gardiner-scholarship/basic-program-facts-gardiner/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

In the 2021–2022 school year, 21,155 children were using accounts.

Step Up for Students, “Family Empowerment Scholarship for Children with Unique Abilities,” August 2022, https://www.stepupforstudents.org/wp-content/uploads/2022.8.10-FES-UA-ESA.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022).

North Carolina. North Carolina lawmakers enacted Personal Education Savings Accounts in 2017, but in the 2022–2023 school year, these accounts will merge with the state’s K–12 private school scholarships for children with special needs (Disability Grants).

North Carolina State Education Assistance Authority, “Education Student Accounts (ESA+) Program,” https://www.ncseaa.edu/k12/esa/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Account holders will still be able to purchase more than one education product or service, a feature of the accounts in every state with such a program. Some students with special needs may be eligible for accounts worth up to $17,000 (an increase from the original account award of $9,000).

Account holders can also participate in the Disability Grant program and the state’s Opportunity Scholarships, which are K–12 private school scholarships for children from low-income families. As of March 2022, 658 students were using an account.

North Carolina Education Assistance Authority, “Education Savings Account Summary of Data,” March 16, 2022, https://www.ncseaa.edu/education-savings-account-summary-of-data/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Tennessee. Tennessee lawmakers allowed children with certain special needs to access accounts in 2015. (The program officially launched in 2017.)

Tennessee General Assembly, 2015 Session, S.B. 27, https://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/BillInfo/Default.aspx?BillNumber=SB0027 (accessed October 31, 2022).

In the 2020–2021 school year, 307 students were using the accounts.

EdChoice, “Tennessee: Individualized Education Account Program,” https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/tennessee-individualized-education-account-program/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

In 2019, lawmakers adopted another ESA proposal, with these accounts available to children in Nashville and Memphis (Shelby County). School district officials sued to force children to remain in assigned schools, but in June 2022, the state supreme court ruled that the program could begin operation in the coming school year. In August, the Chancery Court for Davidson County rejected more motions that would have stalled the program.

Conor Beck, “Court Victory for Parents Defending Tennessee’s Educational Savings Account Program,” Institute for Justice, August 5, 2022, https://ij.org/press-release/court-victory-for-parents-defending-tennessees-educational-savings-account-program/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

New state laws

In 2021, lawmakers in five states adopted new education savings account plans, including two that combined tax-credit scholarships with education savings accounts:

West Virginia. West Virginia lawmakers adopted a proposal that made nearly every child in the state eligible to apply for an account, making it the most expansive account any state officials had approved at that time, and the second-most expansive after Arizona’s universal expansion in 2022.

West Virginia Legislature, 2021 Regular Session, HB 2013, https://www.wvlegislature.gov/Bill_Status/bills_history.cfm?INPUT=2013&year=2021&sessiontype=RS (accessed October 31, 2022).

All students attending a public school in West Virginia for at least 45 days or who are entering kindergarten are eligible to apply for the accounts, aptly named Hope Scholarships.

Lawmakers require students to attend a public school for 45 days because by that time in the school year the student is included in the traditional school funding formula for that year. Then, if the student uses an education savings account, the taxpayer money from the public school formula “follows” the child to an education savings account and no new taxpayer money is needed. If a child was in a private school or homeschooled, new taxpayer money would need to be added to the state treasury to fund that child’s account. If students are required to attend a public school before using an account, the education savings account program will not generate a fiscal note stating that new taxpayer money is required for students to use the accounts.

Similar to the accounts in Arizona, state officials deposit a child’s portion of the state school spending formula into a private account that parents can use to buy multiple products and services.

Each account will be worth approximately $4,300, according to the Cardinal Institute, a research institute in West Virginia.

Cardinal Institute, “Questions from Parents,” https://www.cardinalinstitute.com/questions-from-parents/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Parents can use the accounts for personal tutors and education therapies, along with private school tuition and private online learning programs.

Implementation of the ESA policy was delayed because education industry special interest groups supported a lawsuit to force account holders back into assigned public schools. The state supreme court of appeals agreed to consider the case, and on October 6, 2022, the court upheld the program, removing an injunction that had prevented families from using the accounts.

Brad McElhinny, “Supreme Court Takes Over Hope Scholarship Appeal, Promises Hearing Soon, Says No to Stay,” MetroNews, August 18, 2022, https://wvmetronews.com/2022/08/18/supreme-court-takes-over-hope-scholarship-appeal-promises-hearing-soon-says-no-to-stay/#:~:text=Hearing%20a%20challenge%20to%20the,from%20the%20public%20education%20system (accessed October 12, 2022), and Amanda Kieffer, “Press Release: Cardinal Institute Celebrates Historic Win for West Virginia Families,” Cardinal Institute, October 6, 2022, https://www.cardinalinstitute.com/press-release/wvscoa-upholds-hope-scholarship/ (accessed October 31, 2022).

The program is now fully operational.

Conor Beck, “Victory for School Choice in West Virginia,” Institute for Justice, October 6, 2022, https://ij.org/press-release/victory-for-school-choice-in-west-virginia/ (accessed October 31, 2022).

Indiana. Indiana lawmakers adopted an account proposal that allows children with special needs from low- and middle-income families (i.e., household incomes of up to 300 percent of the income eligibility guidelines for the federal free- or reduced-priced lunch program).

Indiana General Assembly, 2021 Session, HB 1001, https://iga.in.gov/legislative/2021/bills/house/1001#document-dbc2cc8e (accessed October 31, 2022).

Students do not have to attend a public school before applying for an account.

State officials limited funding for the accounts so that only 2,000 students can participate in 2022.

EdChoice, “Indiana: Education Scholarship Account Program,” https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/education-scholarship-account-program/ (accessed October 31, 2022).

New Hampshire. In New Hampshire, officials adopted Education Freedom Accounts in 2021. The accounts are available to students from households with incomes at or below 300 percent of the federal poverty line ($83,250 for a family of four in 2022–2023).

New Hampshire General Court, 2021 Session, HB 2, https://gencourt.state.nh.us/bill_status/legacy/bs2016/bill_status.aspx?lsr=1082&sy=2021&sortoption=&txtsessionyear=2021&txtbillnumber=HB2 (accessed October 31, 2022).

The accounts are administered by a K–12 private school scholarship organization, Children’s Scholarship Fund NH.

Education Freedom Coalition, Education Freedom NH, https://educationfreedomnh.org/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

In its first year of operation (the 2021–2022 school year), nearly 2,000 children used accounts. That amounts to more than 1 percent of K–12 students in the Granite State—a record enrollment, per capita, for the first year of operation of any education choice policy. Each account was worth approximately $3,400. As of September 2022, more than 3,025 students are receiving ESAs worth an average of $4,857.

Children’s Scholarship Fund New Hampshire, “Frequently Asked Questions,” https://1b2.ee8.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/NH-FAQ-2.28.22.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022); Ethan Dewitt, “Education Freedom Accounts Double after One Year; Most Recipients outside Public School,” New Hampshire Bulletin, September 15, 2022, https://newhampshirebulletin.com/briefs/education-freedom-accounts-double-after-one-year-most-recipients-outside-public-school/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Kentucky. Bluegrass State lawmakers created accounts funded by charitable donations to nonprofit, scholarship-granting organizations.

In Kentucky the new ESA Policy allows students to choose from a variety of education products and services in addition to private school tuition.

Kentucky Legislature, 2021 Session, HB 563, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/21rs/hb563.html (accessed October 31, 2022).

Eligible students include children in households with incomes of up to 175 percent of the income limit for the federal free- or reduced-priced lunch program.

The program has restrictive features not found in other states’ account offerings, though. One such feature prevents participants from receiving account funding if his or her household income increases to a figure greater than 250 percent of the income limit for free- or reduced-priced lunch.

EdChoice, “Kentucky: Education Opportunity Account Program,” https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/programs/education-opportunity-account-program/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Another provision states that only students living in large counties (with populations greater than 90,000) can use their accounts for private school tuition.

Lawmakers have not implemented Kentucky’s program yet due to a lawsuit challenging the accounts.

Kentucky Department of Revenue, “Education Opportunity Account Program,” October 12, 2021, https://revenue.ky.gov/News/Pages/Education-Opportunity-Account-Program.aspx (accessed October 31, 2022).

Missouri. Lawmakers in Missouri, as in Kentucky, adopted an education savings account program that is funded via charitable contributions to scholarship-granting organizations.

101st Missouri General Assembly, 1st Regular Session, HB 349, https://house.mo.gov/Bill.aspx?bill=HB349&year=2021&code=R (accessed October 31, 2022).

Individuals will receive tax credits of up to 100 percent of their donations but the amount of credits claimed by any donor cannot exceed half of their annual state tax liability. Only 10 scholarship organizations are allowed to award accounts.

Cameron Gerber, “Parson Signs New ESA Program into Law,” The Missouri Times, September 7, 2022, https://themissouritimes.com/parson-signs-new-esa-program-into-law/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Lawmakers limited the total amount of tax credits awarded to contributors to $25 million in the program’s first year.

Research

Since lawmakers’ adoption of the first account program in Arizona in 2011, research has demonstrated that account holders use their ESAs for more than private school tuition. The versatility of the accounts, which distinguishes them from K–12 private school vouchers, has allowed families to meet their children’s unique needs.

This distinction is important because in states with constitutional provisions that restrict the use of public spending on private learning options (known as “Blaine” amendments), parents’ ability to choose more than one learning option has allowed the accounts to survive judicial scrutiny in state courts that are hostile to traditional vouchers.

Parents’ ability to use ESAs for several education products and services at the same time is crucial for providing quality learning experiences outside the classroom.

In 2013 and 2016, researchers found that approximately one-third of Arizona account holders used their child’s ESA for more than one education product or service.

Lindsey M. Burke, “The Education Debit Card: What Arizona Parents Purchase with Education Savings Accounts,” EdChoice, August 2013, https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/2013-8-Education-Debit-Card-WEB-NEW.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022), and Jonathan Butcher and Lindsey M. Burke, “The Education Debit Card II: What Arizona Parents Purchase with Education Savings Accounts,” EdChoice, February 2016, https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2016-2-The-Education-Debit-Card-II-WEB-1.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022).

Again, parents’ access to textbooks, personal tutors, education therapists, online classes, and more is what makes the accounts unique among private learning options in states around the country.

In 2018, researchers found that more than one-third of account holders in Florida also used the ESAs for more than one purpose. This report also found that among these families purchasing more than one product or service, more than half (55 percent) paid for several products and services and did not purchase private school tuition—making them “customizers” of their children’s educations apart from private schools.

Lindsey Burke and Jason Bedrick, “Personalizing Education: How Florida Families Use Education Savings Accounts,” EdChoice, February 2018, https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Personalizing-Education-By-Lindsey-Burke-and-Jason-Bedrick.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022).

More recent studies continue to substantiate these findings that separate the accounts from traditional K–12 scholarships. In 2021, a study of North Carolina account holders found, for the first time, that a majority of account holders used their child’s ESA for more than one product or service. Sixty-four percent of account holders used their child’s ESA to select more than one education item or service.

Jonathan Butcher, “A Culture of Personalized Learning,” John Locke Foundation, August 13, 2021, https://www.johnlocke.org/research/a-culture-of-personalized-learning/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

This figure is nearly double the share of families using the accounts in this way in the first two studies of ESA usage in Arizona.

This report also found that families using the accounts lived in ZIP codes where the average income was close to the statewide median. Fifty-three percent of account holders—more than half—live in areas in which the median income is within $10,000 of the statewide median. These findings mean that students from families of modest means are benefitting from the ESAs.

According to the report, families using private school scholarships at the same time as they participated in the state’s education savings account options in North Carolina also purchased more than one item or service. In North Carolina, families can access an education savings account and a K–12 private school scholarship option for children with special needs or from low-income families.

Even families that accessed an account and a scholarship used the new opportunities to pay for more than private school tuition, providing evidence that when the accounts are offered to families in addition to scholarships or vouchers, parents will still make education purchases according to a child’s needs.

A 2021 study analyzing Florida account holder spending found that parents continue to customize a child’s education when they remain with an ESA for longer periods. According to researchers Michelle L. Lofton and Marty Lueken, “The longer students remain in the program, the share of ESA funds devoted to private school tuition decreases while expenditure shares increase for curriculum, instruction, tutoring, and specialized services.”

Michelle L. Lofton and Martin F. Lueken, “Distribution of Education Savings Accounts Usage Among Families: Evidence from the Florida Gardner Program,” Brown University EdWorkingPaper No. 21-426, June 2021, https://www.edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai21-426.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022).

The percent of Florida ESA funds that parents used each school year increased from 60 percent in 2015 to 73 percent in 2016 to 88 percent in 2019. During this same period, however, the amount of account funds spent on education products outside of tuition (“instructional materials”) quadrupled. Here again, research demonstrates that parents will customize a child’s learning experience when they have the opportunity to purchase different services and items, and education savings accounts are meaningfully different from K–12 private school vouchers.

Policy recommendations

Eligibility. Lawmakers should give every child in their state the option to use an education savings account—and Members of Congress should do the same for K–12 students in Washington, DC, students living within federal jurisdictions, such as tribal lands and attending Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) schools, and children in active-duty military families.

Limiting account access creates a multi-tiered education system where certain families have more and better learning opportunities for their children than others. Furthermore, research on student achievement after the pandemic demonstrate that millions of children are not performing at age- or grade-appropriate levels and need help gaining essential life and academic skills.

Nation’s Report Card, “Reading and Mathematics Scores Decline During COVID-19 Pandemic,” 2022, https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/highlights/ltt/2022/ (accessed October 12, 2022).

Lawmakers should act with a sense of urgency to help students catch up.

Funding. State officials should transfer a child’s portion of the state education spending formula into a private account that parents use to purchase education products and services. This method is preferable to plans that fund the accounts through annual appropriations, which are subject to legislative spending constraints each year and can require additional taxpayer spending.

Policymakers can follow the models in place in Arizona and now Florida, to name just two, that allow taxpayer spending to follow a child to their public or private learning choices.

Testing. State officials should allow participating private schools to choose the national norm referenced test—such as the Stanford series, the Iowa Test of Basic Skills, or the Classical Learning Test (CLT)—that best matches the institution’s curriculum and report aggregate results after a period of three years. The agency administering the accounts should contract with a survey company to measure parent satisfaction.

These two indicators—aggregate student results over time and parent satisfaction—should serve as the measures of success for account holders. Test results, though, should not determine student or school eligibility for participation in an account program.

Lawmakers should not require account holders to take state tests administered to public school students because such assessments impact instructional choices, thus affecting school officials’ curricular decisions and limiting parental options. Requiring account holders, homeschool students, or private school students to take state tests would produce uniformity, not an account option that allows for customization according to a child’s unique needs.

Conclusion

Every child should have the opportunity to succeed in school and in life. After the pandemic, as researchers report steep learning losses across grade levels and subjects, the call for quality learning options is especially urgent.

National Center for Education Statistics, “Reading and Mathematics Scores Decline During COVID-19 Pandemic,” NAEP Long-Term Trend Assessment Results: Reading and Mathematics, https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/highlights/ltt/2022/ (accessed October 31, 2022), and Clare Halloran, Rebecca Jack, James C. Okun and Emily Oster, “Pandemic Schooling Mode and Student Test Scores: Evidence from U.S. States,” National Bureau of Economic Research, November 2021, https://www.nber.org/papers/w29497 (accessed October 31, 2022).

Education savings accounts empower parents with the ability to meet every family and child’s unique education needs and should be available to all school-aged children. Students need options such as ESAs now more than ever.