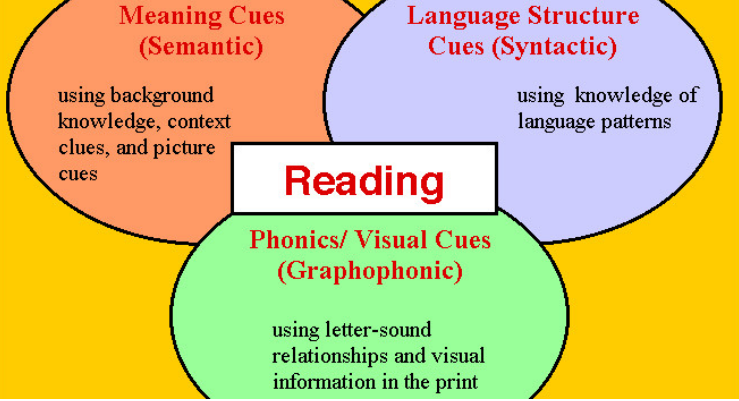

Emily Hanford’s podcast Sold a Story tells the disturbing tale of how schools have come to embrace patently absurd and ineffective methods for literacy instruction. I could summarize one such method, known as “three-cueing,” in one sentence: Teach children how to guess the meaning of a sentence rather than how to read it.

Emily Hanford’s podcast Sold a Story tells the disturbing tale of how schools have come to embrace patently absurd and ineffective methods for literacy instruction. I could summarize one such method, known as “three-cueing,” in one sentence: Teach children how to guess the meaning of a sentence rather than how to read it.

(You can listen to all six episodes of Sold a Story here.)

Despite the implausibility of this strategy – as well as multiple decades of neurological research confirming just how destructive these techniques are – it has a cult-like following among many public-school teachers. As EdWeek reported in 2020:

In 2019, anEdWeek Research Center survey found that 75 percent of K-2 and elementary special education teachers use the method to teach students how to read, and 65 percent of college of education professors teach it.

Episode 4 of Sold a Story, titled “The Superstar,” focuses on Lacey Robinson, an African-American girl in Dayton, Ohio, in the 1970s whose mother insisted she be retained in first grade so she could learn to read. Lacey’s second first-grade teacher taught her to decode words and then Lacey taught her grandmother to read. Inspired, Lacey years later became a teacher with a mission to teach children, especially Black children, how to read.

Lacey Robinson began her career at a Georgia public elementary school where her superiors quashed her efforts to establish a reading program. She moved to a suburban school, hoping to learn what children were offered there, so she could bring it back to inner-city schools.

Along the way, Robinson attended graduate school at Columbia Teacher College and went to work for Lucy Calkins, a leader in three-cueing training. Hanford includes videos in “The Superstar” of teachers fawning over Calkins that are obsequious enough to make 12-year-old Taylor Swift superfans blush.

Robinson found Calkins’ three-cueing system prevalent in suburban schools. But she also discovered that her affluent students’ ability to decode words was made possible because they had tutors.

“They were learning to decode at home with tutors,” Robinson told Hanford. “I know, because I became one of them.”

Okay, so let’s pause the story here and recall how students in the U.S. compare to students around the world in reading and math achievement.

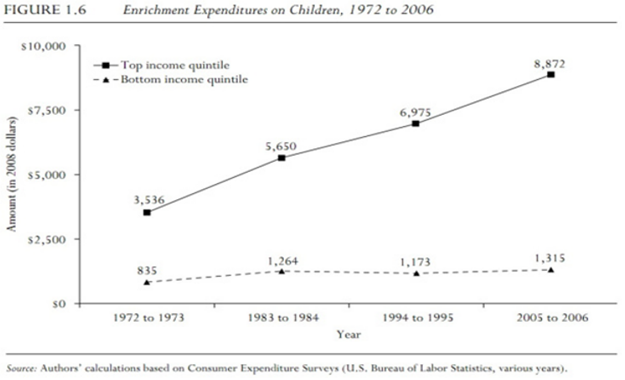

Robinson describes for Hanford an American school system that serves all children poorly but notes that some kids have greater access to private tutoring than others. Americans with the least ability to pay for private remediation score similarly to students in much poorer countries that have greater poverty problems and that fund their school at a much lower level.

Robinson describes for Hanford an American school system that serves all children poorly but notes that some kids have greater access to private tutoring than others. Americans with the least ability to pay for private remediation score similarly to students in much poorer countries that have greater poverty problems and that fund their school at a much lower level.

Well-to-do people simply buy their way out of the problem, a trend scholars have tracked for decades.

I will return to Hanford’s series in future posts and attempt to explain just why the disaster the PISA data illustrates has proved to be so enduring over so many decades. Spoiler alert: It has everything to do with the curricular preferences of the special interest groups that all too easily dominate public education and nothing to do with your interests as a student, parent or taxpayer.

I will return to Hanford’s series in future posts and attempt to explain just why the disaster the PISA data illustrates has proved to be so enduring over so many decades. Spoiler alert: It has everything to do with the curricular preferences of the special interest groups that all too easily dominate public education and nothing to do with your interests as a student, parent or taxpayer.

Lawmakers should and will attempt to stamp out these tragically ineffective practices. The illiteracy Swifty cultists have rope-a-doped their way through such challenges in the past. A bit of rebranding here, two bits of obfuscation there, an application of political power everywhere.

The smoke clears and the three-cueing crowd has yet another generation of Americans training into illiteracy. It has all happened before, and sadly, it will happen again.

While nothing would please me more than to prove him wrong, Einstein’s definition of insanity applies. If you area a parent or a grandparent of a child you would like to see learn to read, I wouldn’t bank on this issue getting resolved any time soon.

The unseen voice is urging you to “Get out!” It’s unfortunate, in the words of Eddie Murphy, that “It’s too bad we can’t stay.”