Aaron Churchill, Ohio research director for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, has released a new report on charter schools in his state for the institute.

Aaron Churchill, Ohio research director for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, has released a new report on charter schools in his state for the institute.

Broadly speaking Churchill praises an effort that began in 2015 to tighten up accountability for authorizers, advocates for funding and other efforts to expand “quality” charters, and calls for funding equalization between brick-and-mortar district and charter schools.

Churchill writes: “Ohio can’t afford to slip back into the dark ages of lax accountability and anything-goes in the charter sector. Lawmakers need to maintain the commitment to accountability for sponsors and schools to ensure that student achievement remains a priority and that the performance of the sector continues its upward trend.”

This bit of text in the study got your humble author’s attention: “Through much-needed reforms, state lawmakers have reinvented Ohio’s charter school sector. The Buckeye State is no longer the “wild west” of charter schools, as dozens of low-performing schools have closed, and more than forty sponsors have departed.”

Out in Arizona, we take the “wild west” term as a badge of honor, given our remarkable results and the unfortunate stagnation of much of the rest of the charter movement. I don’t live in Ohio, and thus will offer no opinion on any of Chu’s recommendations. I will however offer a different perspective.

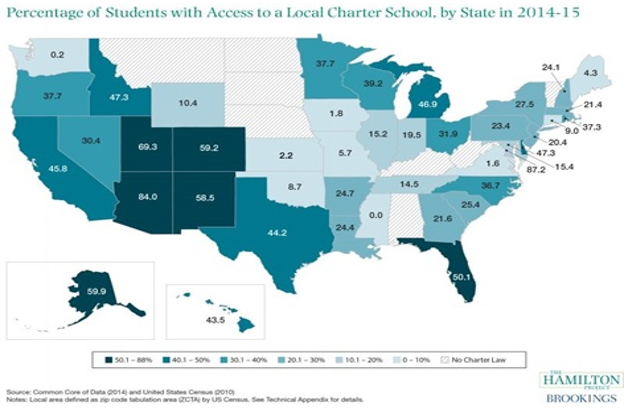

Let’s start with exhibit A, the Brookings charter school access map from 2014-15.

The map shows the percentage of students in each state with one or more charter schools operating in their ZIP code. Even before the 2015 reforms that Chu noted led to 100 Ohio charter schools eventually closing, the state’s charter school sector operated in fewer than one-third of all Ohio ZIP codes.

This was according to the initial design of the Ohio charter statute. Until a recent change in statute supported by both Fordham and yours truly effectively prevented charter schools outside urban areas.

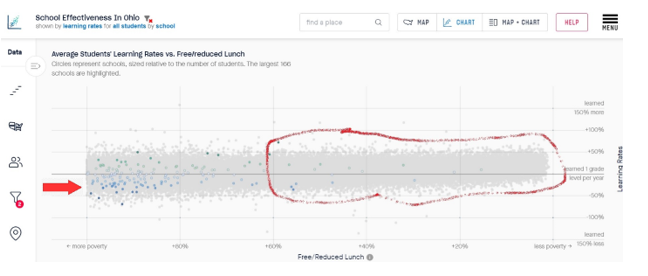

The Stanford Educational Opportunity Project has compiled academic achievement data on schools from around the nation by linking state exams. This chart shows the average rate of academic growth by school for Ohio charter schools, 2008-2018.

Figure 1: Average Academic Growth Rates for Ohio Charter Schools, 2008-2018 (Source: Stanford Educational Opportunity Project)

Figure 1: Average Academic Growth Rates for Ohio Charter Schools, 2008-2018 (Source: Stanford Educational Opportunity Project)

Two things to note: First, the circle. Ohio has very few charter schools with either median or low levels of student poverty. The lack of schools in the red circle constitutes further confirmation of the heavily geographically segregated nature of Ohio’s charter school sector seen in the Brookings map.

Second, note the red arrow. Ohio had a large number of high-poverty charter schools with low levels of average academic growth (blue dots below the “learned 1 grade level per year” line. This is disturbing. It means the already large achievement gaps grew in these schools over time.

Finally, take note of the blue-to-green dot ratio: High grow schools do not outnumber schools with low levels of growth.

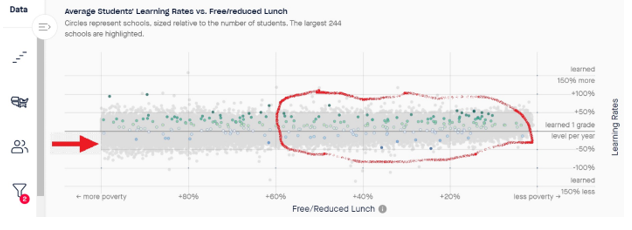

Now, let’s compare Ohio’s geographically segregated charter sector to the nation’s most geographically inclusive charter sector in Arizona. As shown in the Brookings map, 84% of Arizona students had one or more charter schools operating in their ZIP code.

Figure 2: Average Academic Growth Rates for Arizona Charter Schools, 2008-2018 (Source: Stanford Educational Opportunity Project)

Look again in the red circle. Lots of charter schools and lots of charter schools with high levels of academic growth.

Next, let’s examine the high poverty area of the chart near the red arrow: very few low-growth schools.

Finally, notice the total ratio of green-colored schools to blue-colored schools in the entire chart. Arizona has high growth schools across the entire sector, relatively few low-growth schools.

Data from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools reveal that Arizona has a larger absolute number of urban charter schools than Ohio. How did the state avoid a large number of low-growth schools-urban or otherwise? Closures, but largely not of the administrative variety.

The Arizona State Board for Charter Schools listed 106 charter school closures between 2010 and 2014 and the reasons for the closures, a few more than the 100 closed in Ohio since 2015. The board describes a wide variety of reasons for closures including lack of enrollment, loss of a facility, merger with another charter, etc. The explanations are broad enough to require interpretation, but approximately 16 of the school closures involve a clear administrative action by the board to either close or merge.

Arizona charter schools that closed between 2000 and 2013 had an average tenure of operation of four years and an average of 62 students enrolled in the final year of operation for closed Arizona charters. Arizona law grants 15-year charters, but the competitive environment in Arizona closes charters early and often.

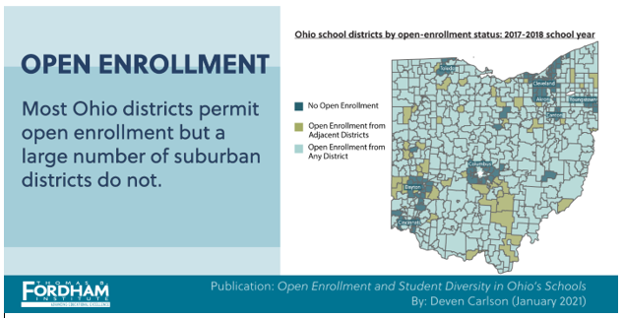

Why does Ohio have so many low-growth charter schools? I believe that this map from the Fordham Institute explains much of the difference between Ohio and Arizona:

Notice that not every suburban district in Ohio participates in open enrollment. Notice also the sickly, green-colored districts that only participate in open enrollment with adjacent districts. One can’t help but wonder just which students they might be trying to avoid.

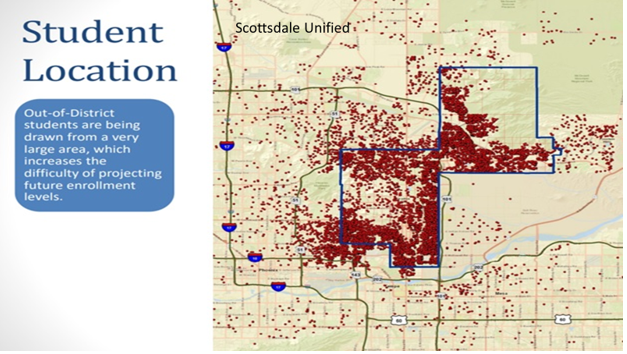

My theory is as follows. Low-growth urban charter schools survived in Ohio but quickly closed in Arizona because Arizona students have lots of other options. Nearly all Arizona school districts participate in open enrollment. This includes relatively affluent districts like Scottdale Unified, which brings in over one-quarter of its total enrollment from outside the district’s boundaries.

Scottsdale Unified enrolls approximately 20,000 students, with 4,500 students coming to the district through open enrollment. The 9,000 students who live within the boundaries of Scottsdale Unified who attend schools in charters, other districts, private schools, etc., doubtlessly play a large role in making open-enrollment opportunities available. Suburban districts in Arizona prefer to participate in open enrollment rather than close campuses.

Arizona’s suburban charter schools opened suburban districts to open enrollment, leading to closure of low-demand charter schools. This virtuous cycle does not have the chance of occurring in charter sectors constrained exclusively to urban areas.

Wisely, Ohio lawmakers recently expanded choice options by removing geographic restrictions on charters and expanding private choice options. The limitations of Ohio’s charter sector thus seem to owe more to poor central planning than to “wild west” liberality.

Author and podcast host Steven Berlin wrote: “The strange and beautiful truth about the adjacent possible is that its boundaries grow as you explore them. Each new combination opens up the possibility of new combinations.”

Arizona’s experience shows that choice programs, far from being siloed, interact with each other out in the field. Allowing families and teachers to shape the K-12 space is a much better idea than leaving it to state officials and is the best solution to the elimination of low-performing schools of any sort: more options.

Embracing liberality takes humility and wisdom, but without it, choice sectors quickly hit a low ceiling in serving the interests of the poor.

Ohio’s charter failure, by my way of thinking lies in central planning. The goal ought not be to replace bad central planning with better central planning. Rather, the goal should be to create a fully inclusive and demand-driven system of education that allows educators and families to act as the hands of a potter at a wheel, molding the K-12 space over time to create the types of schools educators want to run – and that families want to support.