The longer Florida’s private school scholarship programs operated, the bigger the benefits for students in public schools.

That’s the headline finding from a new study published this week in the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy.

Researchers David Figlio, Cassandra Hart and Krzysztof Karbownik have been studying Florida’s school choice programs for years. They sum up their latest findings this way: “We find that as public schools are more exposed to private school choice, their students experience increasing benefits as the program matures.”

Earlier work by Figlio and Hart showed that competition with scholarship programs appeared to drive improvements in public schools, and studies have found similar effects in other states. But those studies looked at newly created or expanded programs.

This new paper looks at the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program over a much longer timeframe, from 2003 to 2018. The program grew sevenfold during that period, and eligibility for the scholarships expanded up the income ladder.

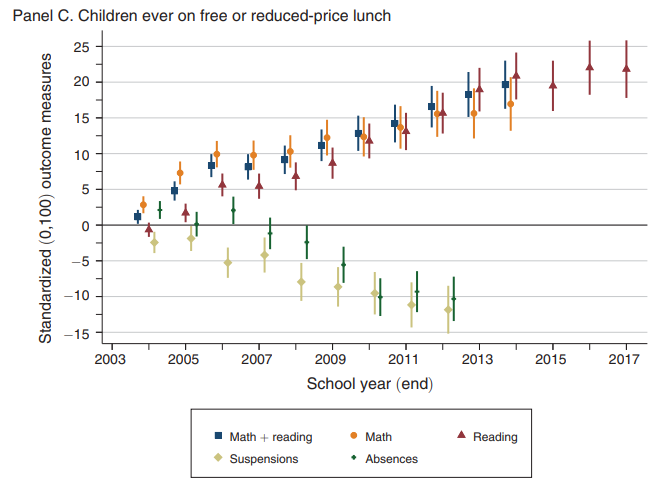

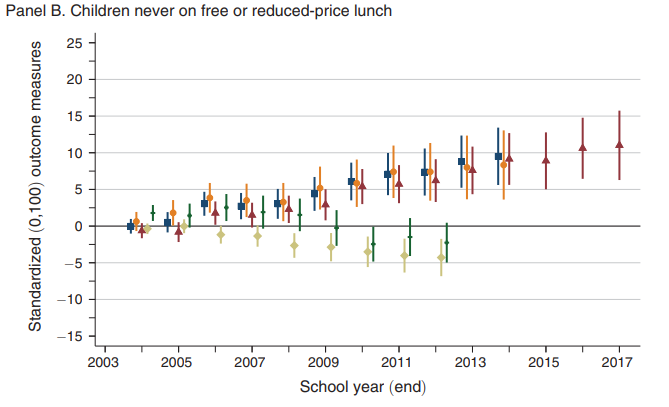

The paper compares student outcomes in highly competitive areas of the state, where students were especially likely to choose scholarships, with lower-competition areas. Public schools in the higher-competition areas saw larger decreases in student absences and suspensions, and larger increases in reading and math scores. These benefits strengthened over time. Some benefits that were not discernible when the program first launched, like the reduction in student absences, took years to develop.

Readers unfamiliar with the Florida landscape might assume this means that increased competition benefitted students in high-density urban districts and left their rural counterparts behind, but the areas with high densities of scholarship participation included the state’s largest urban school district (Miami-Dade County) and its smallest rural district (Jefferson County).

The benefits were uneven in a different way. They appeared stronger for lower-income students who qualified for free and reduced-price lunch (and thus were all eligible for means-tested scholarships).

For other students with higher incomes, many of whom did not all qualify for scholarships, there were still benefits from competition, but they were smaller.

These results tee up some intriguing questions about the state’s changing landscape, especially in the wake of HB 1, which this year made all students eligible for education choice scholarships and produced the largest expansion of scholarship participation any state has seen to date.

Will the benefits of competition be sustained, or even accelerated, with this new expansion? Will increased competition in more affluent areas accelerate public school improvement for higher-income students in public schools, who saw smaller benefits during the era of means-tested scholarships?

There is another set of questions left unanswered by quantitative studies. The numerical results don’t say very much about what’s going on inside schools that face increased competition. Do they improve because students find a better fit? Some data in the paper cast doubt on that explanation, because the composition of public-school students examined in the study does not appear to change very much. Do public school districts respond to intense competition by lowering class sizes or introducing new magnet programs? In some cases, yes, but the researchers also find reason to doubt that those shifts explain the improved results.

The bottom line is that, at least in Florida, growth of private school choice programs can benefit the vast majority of students who remain in the state’s public schools, and those benefits appear to increase over time. Exactly how and why that happens remains a mystery worth exploring.