DAVENPORT, Fla. – Valeria Oquendo didn’t set out to be an entrepreneur. “Ms. V,” as her students call her, had wanted to be a teacher since she was a teenager. On her way to an elementary education degree, she interned at a public school and, initially, those dreams became even clearer.

“Still in my brain I was thinking, ‘I’m going to graduate, I’m going to have my perfect classroom, I’m going to be a first grade teacher,’ “she said.

But then, in education-choice-rich Florida, a funny thing happened.

Oquendo’s “side hustle” became her full-time gig.

When COVID-19 hit in 2020, friends and family begged Oquendo to tutor their children, many of whom were struggling with online instruction. Oquendo was still in college. But before she knew it, she was tutoring 20 kids.

The light bulb flickered on.

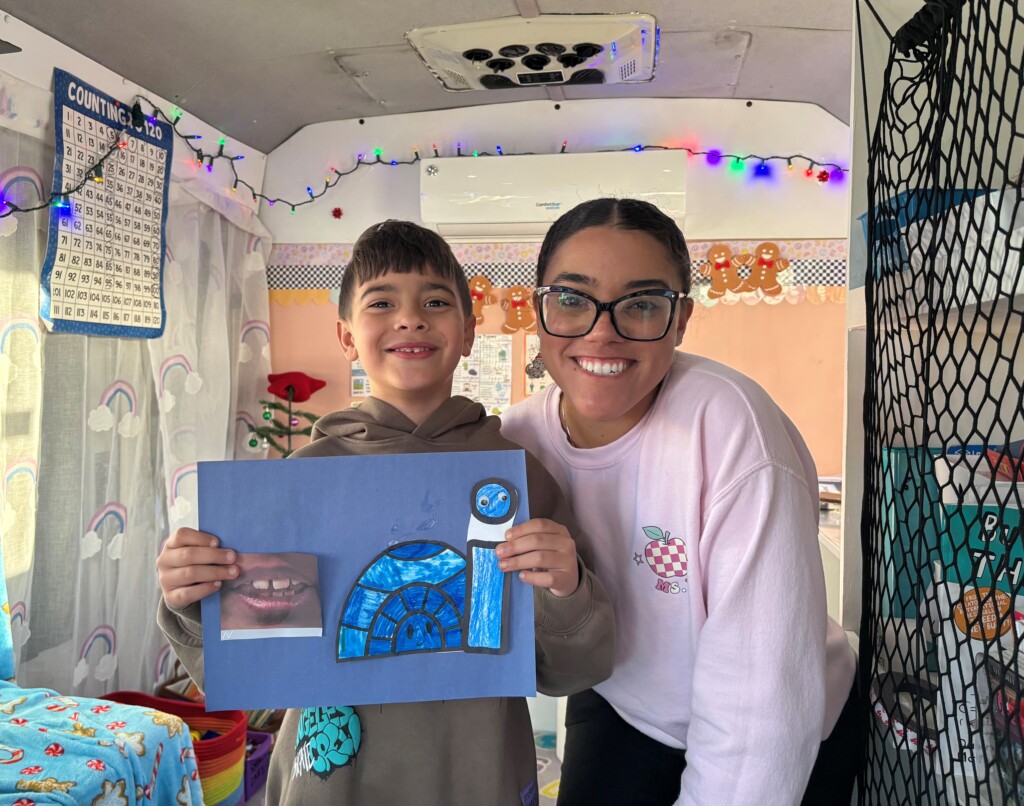

Today, Oquendo runs Start Bright Tutoring, a mobile tutor and a la carte education provider in this insanely fast-growing corner of metro Orlando.

She focuses on elementary reading and math, with 20 to 30 students who are homeschooled or in public schools. A handful use state-supported education savings accounts (ESAs), and it’s highly likely even more will use them in the future.

Demand is soaring. When Oquendo pitched her business on TikTok, mayhem ensued: She racked up hundreds of thousands of views and put 70 students on a wait list before being forced to stop taking calls.

Now Oquendo sees a future outside of traditional schools not only for herself, but for other young educators. As choice continues to expand, she said, more and more can tap into the new possibilities.

“Everybody has their niche,” said Oquendo, 26. “It all depends on the effort and not giving up.”

Florida is humming with former public school teachers who, thanks to choice, have created their own learning models. Their often-inspiring stories (like this and this and this) are becoming commonplace.

Oquendo, though, is the next wave: Educators creating their own options instead of becoming traditional public school teachers.

Oquendo represents a couple of other fascinating trend lines, too.

She’s a niche provider instead of a school, which allows her to serve Florida’s fastest-growing choice contingent: a la carte learners.

Florida has multiple ESA programs that give families flexibility to pursue options beyond schools. With ESAs, they can choose from an ever-growing menu of providers, like Start Bright, to assemble the program they want. The main vehicle for doing that, the Personalized Education Program scholarship, met its state cap of 60,000 students this year, up from 20,000 last year.

Oquendo’s decision to create an option on wheels is also noteworthy.

Florida’s education landscape gets more diverse and dynamic every day. But it’s still rife with frustrating stories about talented teachers trying to set up microschools and other innovative models, only to run into outdated zoning and building codes and/or code enforcers who seem to be curiously inflexible. (Thankfully, some still find happy endings.)

Until those barriers are addressed, going mobile – something choice visionaries suggested nearly 50 years ago – may be one way out.

Oquendo is the daughter of a police officer and an accountant. After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, the family moved to Florida, and she enrolled in the University of Central Florida.

Oquendo said she was fortunate to have an amazing teacher as her mentor when she interned at a public school. But she was also haunted by the moment the teacher told her the class needed to move on to the next unit of study, even though several students, including one with a learning disability and another learning English, were not ready.

“She said, ‘This is what we do.’ “Translation: We have to move on.

That experience pushed Oquendo to choose a different path, too.

Initially she wanted to steer her tutoring venture into a microschool. She found a good location, but the building needed $15,000 in adjustments to meet building codes, and even then, there was no guarantee of a green light from local officials. Oquendo was bummed. Thankfully, her mom came to the rescue, inspired by a mobile grooming service the family uses for its Schnauzers.

“She said, ‘Why don’t you get a van and make it a mobile classroom?” Oquendo said. “I was like, ‘Mom, the kids are not pets.’ “

Upon further investigation, mom was on to something. In the summer of 2021, Oquendo spent $8,000 for a 2014 Ford E-350 shuttle bus, then another $7,000 to turn it into a mini-classroom. Ms. V’s van is complete with desks, bins, lights, shelves, computers – and just about anything else you’d find in a typical classroom.

That fall, Oquendo was up and running, visiting students in their homes. At some point, she realized she could reach more families if she parked at locations that were still convenient – like shopping plazas – and have them meet her there.

Oquendo’s TikToks came just months after she earned her degree. The response was understandable, she said, given that many families lived the same reality she witnessed as an intern.

“It’s the system,” she said. “If it was better, we wouldn’t have the demand.”

Oquendo said many families also respond to her because they share a cultural connection. She was still struggling with English when her family moved to Florida, and many of her students are English language learners, too. She offers living proof they will overcome.

“I tell them, ‘I get you,’ “she said. “I tell them, ‘It’s okay to make mistakes. I love mistakes.’ That way, they’re not afraid.”

Forging her own path has not been all peaches and cream.

At one point, the van engine died, and Oquendo had to find $6,000 to replace it. At another, she invested in solar panels, hoping to cut down on fuel costs for air conditioning. But they didn’t work as she hoped. “I didn’t have a guide,” she said. “I just had myself – and my mistakes.”

At the same time, she said, she takes satisfaction in knowing her students are making progress. And that she has the power to quickly adjust, both for them and herself.

Oquendo is shifting to serve more students whose parents want in-home tutoring for longer stretches. She’s adding Spanish lessons. She’s also offering monthly field trips to places like LEGOLAND and a local farm.

On a whim, Oquendo recently set up gardening lessons for interested families, essentially sub-contracting with an organic farmer. Her students loved it.

In South Florida, similar operators are realizing they fit into changing definitions of teaching and learning and becoming ESA providers themselves.

Oquendo said the challenges to doing her own thing are real. But the freedom to control her own destiny, and to better help students in the process, makes it all worth it.

“I feel happy, blessed, and fortunate to be doing what I love the most,” she said.

PALM BEACH GARDENS, Fla. – Cristina Bedgood, a 15-year former public school teacher, took two years to craft plans for her own private learning center. She knew she needed 40 students in year one to make it work. But in April, when she held her first open house for Curious Innovators of America, she looked out the front door five minutes before the start time and saw … nobody.

Her heart sank.

Her heart sank.

Thankfully, it floated right back up, because in the next few minutes, 30 families appeared. “And every person who walked in the building said, ‘Oh my God, we need this! ‘ ”

The calls keep coming. Bedgood signed up 10 students on one day in August alone. Most of them use state-supported education savings accounts.

Bedgood said the response has been gratifying – and going her own way as a teacher, liberating.

“I needed to be able to break free. I felt like I was being caged,” Bedgood said, referring to traditional schools. “I knew I could do so much, but I was being limited.”

In Florida, a national leader in expanding education choice, it’s tough to keep up with the growing ranks of former public school teachers who are leveraging choice programs to create their own options.

Bedgood said she came to realize she could help more students by creating her own model – in this case, a K-8 tutoring center focused on math, reading, and enrichment that caters to a wide range of students with a wide range of schedules.

She didn’t come to this conclusion lightly.

Bedgood was the instructional coach at a high-poverty, public elementary school for six years. She found the work “exhilarating.” But she also began to have doubts about the best path forward.

Bedgood said she was effective in part because she had a principal who gave her the freedom to veer from district dictates; to “go rogue” when she thought she needed to. Bedgood said she re-ordered and re-focused some parts of the curriculum, doubled down on others, and better aligned it to state standards. She leaned into response boards for formative assessments. She made widespread use of manipulatives that previously were gathering dust.

Her approach worked. The school’s state-issued grade gradually rose from a D to an A. Math proficiency rose from 47 percent to 72 percent.

But Bedgood said she also saw that principals like hers were rare. And that not everybody had high expectations for high-poverty students.

“I knew it. I watched it. I saw kids who were Level 1’s (the lowest level on Florida’s standardized tests) shoot up to proficiency,” she said. And yet, in some places, “the climate was almost like, ‘These kids can’t do it.’ “

Bedgood asked herself: If I rose through the ranks, would I truly be in position to do what works?

Ultimately, she concluded, there was a good chance she wouldn’t be. So, she looked for the exit. She overcame fears about starting her own operation; persuaded her husband, a firefighter; consulted with experts, including other teachers; and found a good location without too much hassle.

Bedgood describes Curious Innovators as a tutoring center and microschool. She opened in April with two students: Her own kids.

Bedgood describes Curious Innovators as a tutoring center and microschool. She opened in April with two students: Her own kids.

The center is 4,200 square feet, in a trim office building framed by oaks and palms. The interior is colorful and comfortable, with giant, geometric puzzle pieces hanging from the ceiling, all of it designed to stimulate creativity. There are separate rooms for reading, math, and STEM, and multiple stations for students to collaborate.

Bedgood employs five instructors, three of them full time. Two are former public school teachers.

All the students are homeschooled.

Some need tutoring in reading and/or math. Some are there for enrichment. Some mix and match from both. Bedgood emphasizes project-based and inquiry-based learning, but each student’s programming is created in tandem with them and their parents.

Reading and math classes are offered three days a week. Enrichment classes include art, music, drama, debate, creative writing, STEM, and entrepreneurship.

Maria Tobon signed up her daughter and son for math, reading, and science this fall after getting to know Curious Innovators during a three-week summer program. They attend full days on Mondays and Fridays.

One of her children uses Florida’s Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities. The other uses a Personalized Education Program scholarship. Both are administered by Step Up For Students.

“The beauty of a tutoring program like Cristina has built is you can hand pick what you need,” said Tobon, a former Montessori teacher who manages a homeschool co-op.

Tobon said between all her children, she has experienced a full gamut of educational options, from traditional public schools to magnet, charter, and private schools. She decided to homeschool after one of her children was diagnosed with cancer, and the COVID-19 pandemic made traditional schooling too risky.

Homeschooling, she said, turned out to be “absolutely mind-blowing.”

“When I took control … they grew in every sense,” Tobon said. “Going back to a full-time program sounds like jail.”

Kristen Collins wanted part-time schooling for her children, too. Her husband travels a lot for work, and homeschooling allows the family to occasionally join him, without missing a beat educationally.

Bryson, 6, and Aaliyah, 8, both use PEP scholarships. They attend Curious Innovators full days on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays.

“It’s just a great happy medium,” Collins said. And her kids “don’t want to leave. They’re having a blast.”

In some ways, Bedgood’s approach to teaching and learning is mainstream.

She follows the “science of reading” for younger students and struggling readers. She uses standardized tests to gauge proficiency. She tends to follow the grade-level progressions laid out in state standards.

The difference is, she has the flexibility to deviate from those tools, or supplement them, in any way she and the parents see fit.

Collins said that approach is working for Aaliyah, who has struggled a bit in math.

“Cristina recognizes that students learn differently, with different modalities. It’s not one size fits all,” she said. Aaliyah “has only been there two and a half weeks, but I can see she’s getting to these higher levels.”

After experiencing what’s possible outside traditional schools, Bedgood said she couldn’t go back.

Giving parents and teachers options, she said, is the best path to progress.

“I want choice to be the primary form of education,” she said. “The change needs to come from out of the system.”

Kassandra Rodriguez uses the Florida Family Empowerment Scholarship for Unique Abilities, an education savings account program, to create customized learning programs for her sons, Zachary, left, and Cameron. They are visiting a park to learn the science behind natural springs. They have also gleaned for mangoes, gone on nature hikes and participated in virtual classes.

Editor's note: This post provides a parent's perspective to supplement our recent white paper, "A Taste of À La Carte Learning," which spotlights the rise of unconventional learning options in Florida. Thousands of Sunshine State parents are now using state-supported education savings accounts to create unique learning programs for their children.

STUART, Fla. — Kassandra Rodriguez thought she could teach her son Zachary to become a better writer, but no. She gave him prompts she thought would spark his creativity – like, If you could make up any flavor of ice cream, what would it be? – only to get one-sentence responses.

Both of Rodriguez’s children, Zachary, 11, and Cameron, 8, have special needs that qualify them for the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Unique Abilities. That ESA, created by the state 10 years ago, gives families the flexibility to direct funding to various educational programs and providers. On average, each one is worth about $10,000 a year.

After doing some research, Rodriguez found a writing teacher on an online platform, Outschool. The teacher lives in Canada. Only three other students attended the one-hour-a-week slot (including, amazingly, another ESA kid from Florida). And Zachary loved it. Sometimes the teacher would kick things off by reading from a graphic children’s novel – say, “Wings of Fire” – then engaging students in a conversation.

“That seemed to get the juices moving,” Rodriguez said.

Soon, Zach was writing inspired, two- to three-page essays. Even better, he could take the class in the car while Rodriguez drove him and Cam to other educational activities.

Stretch that one example to more than a dozen other providers for Rodriguez’s sons, and you begin to see what’s possible with ESAs and a la carte learning.

Florida is on the cutting edge of what’s coming.

Last year, the Sunshine State moved to universal education choice. But even before that historic shift, thousands of parents were customizing their child’s education, using ESAs to mix and match from a growing universe of providers. Together, these parents and providers are pioneering new approaches to teaching and learning that bypass traditional schools. Homeschoolers have been doing that for decades. But now, with state support, even more families can give it a go, in numbers big enough to ripple through the entire system.

With ESAs, “You can make whatever education program you want,” Rodriguez said. “After meeting more people, and seeing what’s out there, I realized I can make things happen. I can have what I want for my boys.”

What Rodriguez wants includes two of the la carte providers featured in our new white paper, “A Taste of A La Carte Learning.” Both Surf Skate Science and Eye of a Scientist offer popular and hands-on approaches to science instruction.

But the family’s a la carte adventure hardly ends there.

Zachary is diagnosed with dyslexia, ADHD, and a speech disorder. Cameron also has a speech disorder.

Before the family moved to Florida from Iowa in 2020, Zachary had been enrolled in a private school, where he experienced bullying and fell behind academically. That experience is what led Rodriguez to try homeschooling.

Rodriguez uses her sons’ ESAs to pay for speech therapy from the same therapist they used in Iowa, only now they access the services online. Ditto for Zach’s dyslexia tutor. Both of those individuals have credentials that make them eligible for Florida ESA funding.

Rodriguez is also using the ESA to “unbundle” individual classes at nearby schools.

ESA enthusiasts have been talking up this possibility for years. In Florida, thousands of schools, including public schools, could unbundle their services if they wanted. A few examples of that are happening here and here.

Rodriguez asked several microschools if they’d let her boys take a few classes instead of enrolling full time. Some rejected the idea. But a couple said, “Yeah, we can do that.”

At one, both boys took several classes, including “simple machines” for Zach and “collaborative building” for Cam. Both involved science and engineering instruction. At the other, both boys took art and theater. The latter class met weekly for two hours for a semester, and it culminated in a community production of “Aladdin.”

There’s more. The ESA pays for Zach’s membership on a competitive traveling LEGO robotics team. And for both boys, it’ll soon pay for recreational league lacrosse and piano lessons with a music teacher.

Rodriguez uses the ESAs for art supplies, science kits, a book club, and BitsBox, a subscription service that teaches computer coding. She’s also purchased a variety of home education curricula and supports, including Power Homeschool, All About Reading, Singapore Math, and Story of the World.

“I overlap some curriculum because I’m afraid I’m leaving something out,” she said.

Kassandra Rodriguez and her sons are often on the go. One program allows Zachary to learn while she drives the boys to other activities that make up their customized learning programs.

The ESAs, Rodriguez said, incentivize bargain hunting. For example, she considered enrolling her boys in a writing class at a third microschool. But the classes cost $70 an hour, while the Outschool course was $14 an hour. She and the boys also tried out another writing teacher – this one in England – but they didn’t think she was as engaging as the one in Canada.

Blazing trails on the choice frontier isn’t easy.

Zach and Cam’s schedule requires a lot of time and mileage. Their programs and providers are scattered across three counties. Some are an hour from their house.

Rodriguez is a stay-at-home mom, in part because a traffic accident a decade ago resulted in long-term injuries that keep her from working. But it’s a mixed blessing, because the situation has allowed her to devote more time to her kids’ educational needs. Also, Rodriguez’s husband is a surgeon. She knows her family can pay upfront for educational expenses and await reimbursement from the ESA in ways that some families can’t.

Still, Florida’s increasingly choice-driven education system is moving toward greater equity. Every year, more families, particularly those disadvantaged by poverty or disability, gain more power to direct education dollars the way they think is best.

Rodriguez has no doubt this approach works for her family.

She frequently gives her sons tests, and they often showcase their knowledge with projects and presentations. Rodriguez also recently used ESA funds for her boys to take the Iowa Test of Basic Skills, a common standardized test. She said she wants to know how they’re doing relative to students their age and whether her approach is working.

Florida law does not require students like Zach and Cam, who are using the FESUA scholarship, to take a standardized norm-referenced test in reading and math. However, such testing is required for students using the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Educational Options, and the Personalized Educational Program scholarship. The latter is a new ESA, created in 2023, for students not enrolled full-time in public or private schools and whose parents are customizing their education programming.

Rodriguez said she knows from other assessments that Zach is now reading in the 80th percentile for his age, far ahead of where he was in his prior school.

“I like that we can learn what we want – and at our own pace,” she said. “I saw Zachary struggle a lot with his dyslexia. Now he’s right where he’s supposed to be.”

Being able to access what Zach needed, when he needed it, was big. “Whatever it is, we can nip it in the bud,” Rodriguez said. “We don’t have to wait. It’s instant. We can just get a tutor and go.”

Flexibility has other benefits.

Last year, the family made multiple trips to Texas to see Rodriguez’s father before he passed away. Each time, they stayed a week or two, quickly making arrangements that might have been more difficult for a family tied to traditional schooling.

Rodriguez has told her boys they can go to a traditional school, and she’s shown them some possibilities. But so far, they have shown no interest. Truth be told, they think some of the traditional schools look like jails.

“With the amount of freedom and the amount of things we’ve gotten to do,” she said, “I don’t think we could go back.”

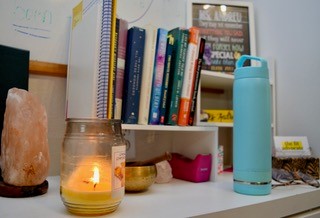

A scented candle lends some ambiance to Lexa Duno's garage classroom. Duno left her job as a teacher in a traditional private school in 2020 to start The Lit Advocate, a tutoring business that focuses on reading, writing and language arts. She and her brother, Carlo Andreu, started edTonomy, an app that helps education entrepreneurs manage their businesses. Photo by Tom Jackson

Lexa Duno became an educational entrepreneur before educational entrepreneurialism was cool, or even a thing. In 2015, as a fifth-grade teacher in a Tampa private school, Duno thought she was where she belonged. It certainly was the place for which her education and training had prepared her.

Even so, she felt a pioneer’s tug, imagining somewhere, somehow, there was a better fit for her skills and temperament. A bilingual literature expert with a degree in creative writing and a passion for poetry, Duno ached for a professional world where she could support students who struggling with literacy or who were challenged by learning disabilities by using evidence-based interventions based solidly in the science of reading.

When coronavirus pandemic came, changing everything, it was not necessarily for the worse. For Duno, it was a time for confronting the hunger that threatened to devour her sense of purpose. In September 2020, she leapt, leaving her job and its regular paycheck to start a home-based literacy tutoring business as — ta da! — The Lit Advocate.

As a teacher, Duno was reborn. Nowadays, her enterprising teaching life is headquartered in a cozy classroom carved from a garage at her blended family’s home on a shady street in Dade City, Florida. Some students she meets in person; others she instructs via internet video. Some of her students benefit from state education choice scholarships managed by Step Up for Students, which hosts this blog.

Duno also worked last year at nearby Cox Elementary School, where she served as a part-time academic intervention tutor in reading and math for students in kindergarten through fifth grade.

As if this sundae needed whipped topping and a cherry, there’s also this: Setting her schedule enabled Duno to publish “They Will Ask: A Story About Embracing Our Differences” in September 2022, an illustrated children’s book about taking pride in an individual’s culture, language, and origins.

And that might have been that, except for this: Duno was made for educational entrepreneurism. As her business blossomed and her referrals boomed, much to the delight of the creative right side of her brain, her left brain was swamped by disorganization. The time-honored tools of teaching, handwritten calendars, ledgers, notes, grade books, were no match for the demands of a freelance educator.

Here’s Carlo Andreu, Duno’s business partner and younger brother: “Lexa started to grow her business, but when she realized … to scale that business … she needed to streamline some of her business administration.”

Which brings us to edTonomy, the app thousands of teachers who, like Lexa Duno, never imagined they needed until they

Florida education entrepreneur Lexa Duno, with her brother, Carlo Andreu. The two founded edTonomy, a classroom organizer app that helps teachers navigate their business operations. Photo by Tom Jackson

launched their own education shops, only to discover, when it came to digitally organizing a free agent’s classroom, there was no app for that.

“We were seeing Facebook comments,” Andreu said, “and comments all over the internet, really, from teachers who were going in the same direction as Lexa, or at least looking for a way to go in that direction.”

And all were saying the same thing: I just want to teach the kids. Where’s the program that will help me organize all the other moving parts — a sort of QuickBooks-meets-Outlook-meets-Microsoft Office-meets-Excel-meets-schoolhouse-Tinder, all swaddled in a Mister Rogers cardigan?

Like Lexa, Carlo favors independent entrepreneurship. So, while he was working for an investment firm in Tampa, he was also looking for an opportunity to launch a tech company. His sister’s frustration, the tip of the teacher tsunami visible just above the horizon, was preparation meeting the moment.

“If what you’re looking for doesn’t exist,” Andreu said, “you’ll have to create it.”

In development for more than a year, edTonomy 1.0 launched in May. Having listened closely, Andreu and the team’s developer, Robin Fowler, digitized everything Duno said she needed, creating a classroom in an app.

Andreu describes it as “a professional tool to manage administrative tasks, support students and their families, and cater to the unique needs of a non-classroom teacher.”

“We’ve put our heart into building a tool that’ll empower educators to see just how valuable their skills, and they themselves, truly are,” Duno said.

Among the edTonomy highlights:

The app is available by subscription, with monthly plans beginning at $39.

With the landscape of school choice changing almost daily, backed by game-changing momentum for education savings accounts, Duno said the time is ripe for education entrepreneurs, those who love to teach, but who increasingly find the traditional classroom stifling. Not that everybody “gets it” just yet.

“We have spoken with investors,” Duno said. “They've said, ‘But educators aren't entrepreneurs.’ ” Here, a meaningful eye roll. “This is something that's extremely frustrating for us. I'm an educator, and I learned to become an entrepreneur, and that's exactly what we're intending to do; we're intending to help teachers who are ready to leave the classroom.”

Instead of finding another outlet for their desire to teach, however, these classroom refugees choose sidetracks that take them out of education altogether.

“We want to help teachers think that there's another option,” Duno said. “You can continue to teach, especially now in a state like Florida” which recently adopted universal ESAs, allowing all K-12 students financial flexibility in their education choices.

With those options for students come opportunities for teachers, Duno said. “They will have the ability to work with a bunch of different kinds of students and to do it without having all that comes with working in the system.”

And for those who don’t want to reinvent the wheel, there’s edTonomy to help them navigate the business side of their brave new career.