Editor’s note: redefinED is supporting National Autism Awareness Month each Saturday in April by reposting articles from our archives that celebrate those who champion the educational rights of children with autism. Today’s post, which originally appeared in March 2018, features a couple whose desire to help their son led them to open an education center for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

By Livi Stanford

Michelle Dunham was troubled as she watched her son, Nick, struggle in school.

He had autism and was grouped in a classroom with children with different learning disabilities at a public school.

Dunham described her son as a gentle giant who hovers around 6’3. But he's also non-verbal. She felt he needed one-on-one support to succeed academically. She didn't fault his teachers, who were doing all they could to help. But to thrive, Dunham said, he needed an intensive learning environment.

“They had no resources to support him,” she said.

She talked things over with fellow parents. They encouraged her to start a school of her own.

Dunham and her husband opened the Jacksonville School for Autism in 2005, as a nonprofit K-12 educational center for children ages 2-22 with Autism Spectrum Disorder — a neurological condition characterized by a wide range of symptoms that often include challenges with social skills, repetitive behavior, speech and communication.

In 2007, the CDC reported 1 in 150 children were diagnosed with autism. Now, 1 in 68 children get diagnosed.

Dunham views the school as one part of a growing societal recognition that, with the right support, people with autism can flourish.

She started the school with the Schuldt family, which has an autistic daughter named Sarah.

“We were two families that could not find the right environment for our children,” Dunham said. “Our kids needed to have more intensive therapeutic support. We wanted it to be an environment that was full of enrichment and resources: a safe environment for kids to learn.”

Individualized learning

Since its founding, the school has blossomed, with 51 students and 50 therapists and classroom teachers. With a 22,000-square-foot building and funding entirely from donations and student scholarships, the school is close to maxing out its space. Ten JSA students receive a Gardiner Scholarship from Step Up For Students, which publishes this blog. Meanwhile, 35 students receive McKay scholarships and six students pay out of pocket.

Dunham said Nick has excelled at the school. Within three months, he started reading.

“He has been able to be participative in his world, because he understands,” Dunham said. “He has been able to show us his intelligence in so many ways.”

The school focuses on helping children with autism and their families by channeling all available resources into supporting students, and by embracing what Dunham calls “outside-the-desk” thinking.

“Children are unique in their learning ability,” Dunham said. “We want to make sure that we leave no stone unturned as far as trying to reach them. If it requires a natural teaching environment, we do that. Whatever it takes to help them.”

The school’s model blends highly structured classroom teaching environments and ABA clinical therapy. Applied Behavioral Analysis is a therapeutic approach that helps people with autism improve their communication, social and academic skills.

Chrystal Ramos, a clinical therapist at the school for the past two years, said lesson plans are tailored to students’ individual needs.

“When I was teaching at different schools that had lesson plans that we had to follow, it was not catered to each child,” she said. “A lot of students that were having trouble were falling through the cracks. We couldn’t focus on their needs. It was following the lesson plan.”

Trina Middleton, educational director at JSA, said many children have “splinter skills.”

They might master higher-level skills in a subject area without being able to demonstrate lower-level skills that educators typically view as building blocks.

For example, a student might be able to add or subtract numbers, but still struggle to match the number seven with a group of seven objects on the table – a concept known as 1:1 correspondence.

Many of the students work one-on-one with a teacher or therapist for half-day or all-day sessions. They also take part in an array of other activities such as music therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, yoga and karate.

Programs like music therapy are designed to cater to students’ interests, while also meeting their therapeutic needs.

“Many individuals with autism have an affinity for water and music,” Dunham said. “One of the things that we have been able to see with our music therapy program is that music for our students doesn’t just grab their attention. It has a healing property to it.”

Building social skills

During a recent visit to JSA, a teacher was dressed up as a painter to engage with students.

Krista Vetrano said she uses costumes to help introduce topics in a fun and creative way — a technique she calls "social modeling."

Vetrano said she tries to make the characters relate to the topic of the lesson. Characters like Pablo Punctuation or Nanny Noun help teach grammar concepts. They give students the opportunity to ask questions practice getting to know someone different and new.

While the school embeds academics everywhere, the staff is focused on one long-term goal: helping students assimilate to the outside world.

For example, if a student has a fear of public restrooms, they visit the restrooms as a first step in helping the child to overcome his or her fear.

The school uses role-playing to help students understand how to greet people or handle situations like waiting in line.

“It is about making their world bigger and bigger,” Dunham said.

Ready for work

The school also implemented a vocational training program for older students to help them acquire skills to become gainfully employed in the future.

Dunham said she began the program because she wanted Nick to thrive as a citizen. Now she wants to expand the program to allow as many individuals as possible to gain skills.

“Our goal is not only train (students), but also to help them seek employment and retain employment,” Dunham said.

Dunham said at the end of the day the school will grow as needed to support the student base.

“We don’t want to grow at the expense of quality,” she said. “We want to make sure we don’t change the culture of learning we worked so hard to build for our students and their families.”

Nick takes part in vocational training at Publix.

His mother describes him as an anxious young man who has difficulty standing in one place. He craves order.

His job at the grocery store is to stack fruit on the shelves, which Dunham described as a perfect fit for him.

“When he goes into Publix and puts his apron on there is a calmness about him,” Middleton said. “He is actually participating and being expected to be responsible for a job that he enjoys and plays to his skill set. His pacing and anxiety decrease.”

Dunham said her son craves social interaction.

“He really loves to be around people,” she said. “That is one of the reasons he enjoys Publix.”

Life with autism

Kristopher Turcotte recently moved with his wife and son from South Carolina to Jacksonville. He was looking for options for his 8-year-old son, who has autism.

“This was one of the best options that we could find,” he said of JSA.

Since his son has enrolled in the school this summer he has acquired more speech.

“He has problems with social settings,” Turcotte said. “That is one of the things that the school has worked with him on."

Dunham explained some students with autism also suffer from food allergies and sleep deprivation, or have a sensitivity to light and sound.

While all teens struggle with puberty, Dunham said for students with autism it is a “mountain to climb.”

She explained many teenagers with autism do not understand what is happening to their bodies. Some develop seizures.

“Puberty can bring out anxiety and aggression in our children,” she said. “We work with the children trying to obviously look for these indicators and what is happening in their life and try to support them first.”

Dunham worries as they grow up and leave school, they may not have all the support they essentially need.

“What is the next step for these students?” she said.

The statistics about increasing autism diagnoses only highlight the urgency for Dunham to develop a working community to support young adults with autism as they transition to adulthood.

“I am looking at a lifespan model that would provide the educational, vocational and residential support for our young adults,” she said.

Editor’s note: redefinED is supporting National Autism Awareness Month each Saturday in April by reposting articles from our archives that celebrate those who champion the educational rights of children with autism. Today’s post, which originally appeared in June 2018, features a dedicated teacher who refused to give up on a child with profound autism.

By Livi Stanford

Abigail Maass never spoke. It was hard for her to connect with others. She grew impatient easily.

Her struggles mirrored those of children everywhere who grow up with profound autism.

This all changed when she met Trina Middleton, a teacher with Duval County Public Schools.

Middleton said she consistently encouraged Abigail and gave her many opportunities to do different activities. She also enrolled her in intensive Applied Behavioral Analysis therapy. ABA is a therapeutic approach that helps people with autism improve their communication, social and academic skills.

“It is just believing in her abilities and supporting her and celebrating with her,” she said.

Priscilla Maass, Abigail’s mother, said Middleton’s belief in her daughter made all the difference.

“She is patient but is firm and the kids react to that,” she said. “She can think outside the box. She can come up with different techniques.”

According to Maass, Abigail has grown substantially in the 10 years that she has worked with Middleton, who now serves as the education director of the Jacksonville School for Autism.

According to Maass, Abigail has grown substantially in the 10 years that she has worked with Middleton, who now serves as the education director of the Jacksonville School for Autism.

Now, Abigail, 12, can use some sign language to communicate, especially about her feelings. She uses her iPad more frequently as a communication device. She finds productive activities at her school, such as helping in the lunchroom. She is also now able to feed herself.

Maass said that in Middleton, Abigail has found an educator she trusts.

“She gets her out of her shell,” she said. “She does not get offended when Abigail will tell her to go. When she needs someone to rely on, Abigail tends to go toward Trina.”

Parents and administrators describe Middleton as dedicating her life to children with special needs. At the Jacksonville School for Autism, Middleton has been credited with expanding classroom programs and for developing a bridge program with the goal of helping transition students from JSA into typical learning environments.

“She is the voice of calm in the storm of Autism for our families and staff, and her presence simply makes everyone in our school program more confident in their capabilities,” said Michelle Dunham, JSA’s executive director. “A true testament to her strength as a leader can be seen in the relationships she maintains today with so many teachers she worked within both public school and JSA.”

Middleton began her career in 1993, teaching emotionally disturbed children in St. Johns County.

She took some time away from teaching to raise her own children. In 2003, she began teaching at Duval County Schools. After four years, she became a site coach for schools that have self-contained classes for students with autism.

That lasted until 2012, when massive budget cuts were made to the school budget.

Middleton said she could not look her parents in the eyes and tell them their children were getting all they needed. She felt the budget cuts fell disproportionately on special needs programs.

The cuts, implemented in 2011, affected classroom curriculum and supplies as well as direct services in speech/language and occupational therapies. They also affected training for staff who worked with children with autism in the classroom.

Student-to-teacher ratios rose, sometimes 5 to 1 in self-contained classrooms, Middleton said.

And she had other ideas about how to change education for students with special needs. She wanted more instructional flexibility than the public school allowed.

“Students’ self-regulation and communication needs to be the focus prior to the focus being on academic areas,” Middleton said.

After learning of the budget cuts, Middleton decided to change course. She took a job at the Jacksonville School of Autism, a nonprofit K-12 educational center for children ages 2-22 with Autism Spectrum Disorder — a neurological condition characterized by a wide range of symptoms that often include challenges with social skills, repetitive behavior, speech and communication.

Founded by Dunham and her husband, the school continues to thrive with 51 students and 50 therapists and classroom teachers. The school also implemented a vocational training program for older students to help them acquire skills to become gainfully employed.

Serving as educational director, Middleton said she is most proud of her ability to establish a strong collaborative relationship between the school’s classroom and clinical staff, tailoring instruction to overcome each student’s individual challenges.

She frequently brings the entire clinical and classroom teams together to discuss students’ needs and progress.

Asked what is the most important thing that educators must do when they teach those with autism, Middleton said it is essential to respect them as human beings with intellectual capacities that far exceed their ability to communicate.

Students like Abigail Maas can attest.

Editor’s note: redefinED is supporting National Autism Awareness Month each Saturday in April by reposting articles from our archives that celebrate those who champion the educational rights of children with autism. Today’s post, which originally appeared in November 2015, relates the story of a South Florida mom who refused to give up until she found the right school for her daughter.

by Travis Pillow

When Charleen Decort was looking for the right school for her daughter, she traveled around South Florida, looking at factors some parents rarely consider, like the color of the walls and the shade of the lights.

When she found her current school, a predecessor of what is now Connections Education Center of the Palm Beaches, another factor carried the day: Trust.

"She has to feel comfortable around you," Decort said of her daughter, who has autism, "and they take the time to do that here. That's big."

She got on the waiting list for the school's early learning program. If a spot hadn't opened in time for kindergarten, Decort said she would have considered teaching her daughter at home, or even moving somewhere else.

Fortunately, she found a place for her daughter, now in third grade, in a growing array of small schools, some public, some private, that are purpose-built to serve children who might be distracted by the flickering of a fluorescent bulb, or rely on an iPad to communicate, or have other special needs that can be hard to accommodate in traditional schools.

Connections — currently a private school, with a charter application set to be approved later today by the Palm Beach County School Board — is a newcomer to this sector-agnostic niche, which caters to children with autism.

Debra Johnson helped start Connections this year, after the Renaissance Learning Center, where she had been principal, moved north to Jupiter. It's now housed in a world-class facility at the Els Center for Autism, as first reported by the Palm Beach Post. Johnson and several other employees launched the new school in West Palm Beach to accommodate parents who couldn't make the drive to the north end of the county.

Other schools have sprung up in surrounding communities, with different emphases but similar goals. There's the Palm Beach School for Autism, a charter school in Lantana. Mountaineers School of Autism is a K-12 private school in West Palm Beach. Oakstone Academy promotes inclusion for special needs students.

Johnson said there's enough demand to support diverse options. Schools like hers can serve a limited number of students, and want to keep student-to-staff ratios low. Connections currently serves slightly more than 20 students, with a student-to-staff ratio of about two-to-one. Its charter application suggests it could eventually grow to 85 students in grades K-8.

"We want to stay small," Johnson said. "We picked the name Connections Education Center because that's our mission — to be connected with the parents and the community."

One recent morning, older students were communicating with teachers using a TouchChat iPad app. Across the hall, other students worked on art therapy, building models of their hands with clay.

In an adjacent room, some of the school's youngest students listened to the "Wheels on the Bus." One child focused his gaze on the pages of an accompanying book. One sat still, bristling at the loud noise. One cracked a smile and started dancing to the music.

Three children, sitting just a few feet from each other, were having completely different reactions. That, Johnson said, is why individual attention can make a difference.

"If you've met one person with autism, you've met one person with autism," she said.

The school can afford to hire extra staff thanks in part to its benefactors. Johnson said Connections started with financial support from a "very generous angel" who has a family member with autism but wants to remain anonymous. Its narrow focus also helps it apply for grants. According to its charter application, the school "has the backing of two family foundations and other community partners to assist in bridging the gap between public and private funding."

Decort, who also serves as the school's parent liaison, said the result is a school that is "more family-like," that can "tailor (instruction) to what your child needs," and that helps children prepare to live independently. It takes students on shopping trips and out to restaurants, to help teach life skills they'll need as adults.

"She doesn't need a babysitter," she said of her daughter. "She needs someone who will challenge her."

Abigail Maass never spoke. It was hard for her to connect with others. She grew impatient easily.

Her struggles mirrored those of children everywhere who grow up with profound autism.

This all changed when she met Trina Middleton, a teacher with Duval County Public Schools.

Middleton said she consistently encouraged Abigail and gave her many opportunities to do different activities. She also enrolled her in intensive Applied Behavioral Analysis therapy. ABA is a therapeutic approach that helps people with autism improve their communication, social and academic skills.

“It is just believing in her abilities and supporting her and celebrating with her,” she said.

Priscilla Maass, Abigail’s mother, said Middleton’s belief in her daughter made all the difference. (more…)

Michelle Dunham was troubled as she watched her son, Nick, struggle in school.

He had autism and was grouped in a classroom with children with different learning disabilities at a public school.

Dunham described her son as a gentle giant who hovers around 6’3. But he's also non-verbal. She felt he needed one-on-one support to succeed academically. She didn't fault his teachers, who were doing all they could to help. But to thrive, Dunham said, he needed an intensive learning environment.

“They had no resources to support him,” she said.

She talked things over with fellow parents. They encouraged her to start a school of her own.

Dunham and her husband opened the Jacksonville School for Autism in 2005, as a nonprofit K-12 educational center for children ages 2-22 with Autism Spectrum Disorder — a neurological condition characterized by a wide range of symptoms that often include challenges with social skills, repetitive behavior, speech and communication.

In 2007, the CDC reported 1 in 150 children were diagnosed with autism. Now, 1 in 68 children get diagnosed.

Dunham views the school as one part of a growing societal recognition that, with the right support, people with autism can flourish.

She started the school with the Schuldt family, which has an autistic daughter named Sarah.

“We were two families that could not find the right environment for our children,” Dunham said. “Our kids needed to have more intensive therapeutic support. We wanted it to be an environment that was full of enrichment and resources: a safe environment for kids to learn.”

Individualized learning (more…)

Florida's newest private school choice program is no ordinary voucher, a new report finds.

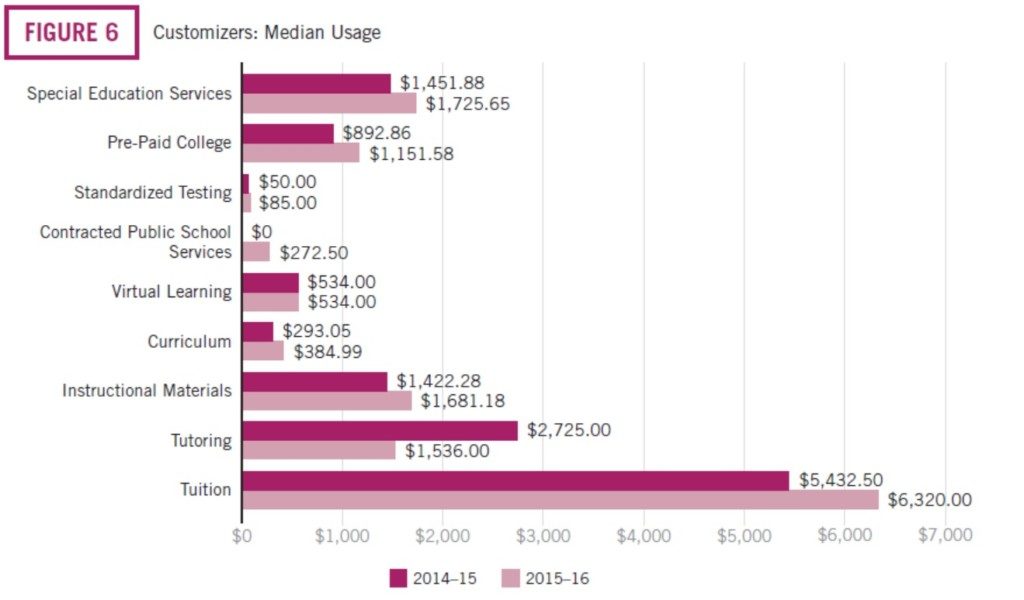

The analysis, released this week by EdChoice, found that in the first two years of the Gardiner Scholarship program, roughly four out of ten parents used the scholarships to pay for multiple educational services — not just private school tuition.

The scholarship program is available to children with specific special needs. It has grown to become the nation's largest education savings account. The accounts allow parents to control the funding the state would spend to educate their child. They can spend the money on a range of education-related expenses, from textbooks and school tuition to tutoring and therapy.

Step Up For Students, which publishes this blog, helps administer the scholarships and provided the data used in the report.

During the 2015-16 school year, 42 percent of parents were "customizers" who used their scholarships for multiple education-related expenses. Source: EdChoice

Educational choice advocates have embraced ESAs because they're more versatile than conventional vouchers. Lindsey Burke, director of the Center for Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation and one of the report's authors, said data suggests parents appreciate that flexibility.

Florida lawmakers are taking steps to make it easier for parents to enroll in the state's voucher program for children with special needs.

Rep. Rene Plasencia, R-Orlando, spoke passionately about the proposal before the House K-12 Innovation Subcommittee gave it a green-light Tuesday.

Right now, the law requires children to enroll in public schools for at least a year before they can receive a McKay Scholarship. Plasencia is the sponsor of HB 829, which would cut that waiting period down to one semester.

He said the public-school attendance requirement has kept some students with the most complex disabilities from getting scholarships. His wife works with some of those students. Advocates have pushed for years to go further than Plasencia's bill, and eliminate the public-school attendance requirement entirely.

"It doesn't necessarily solve all the issues we have, but it is a step in the right direction," he said. (more…)

Florida lawmakers are advancing bills that would make it easier for parents of special needs children who use vouchers to attend private schools to update their evaluations.

Funding for students who receive McKay Scholarships is tied to the evaluations students can receive from school districts every three years. But state Sen. Dana Young, R-Tampa, said sometimes students who use the scholarships need to update their evaluations more often.

For example, if students participate in a school district hospital/homebound program, and then want to move to a private school using a voucher, they could receive McKay Scholarships worth just a few thousand dollars. That's because per-pupil funding for hospital/homebound is typically a fraction of the funding public schools would receive to educate the same children. As a result, scholarships for those students may be less likely to cover the cost of private school tuition. (more…)

Note: See a detailed response to the Orlando Sentinel from Step Up For Students here and a quick summary here. Step Up helps administer Florida's Gardiner and Tax Credit Scholarship programs, and publishes this blog.

One of the schools singled out by the Orlando Sentinel’s investigation of private school scholarship programs was founded by a couple who grew frustrated when their son, burdened with severe medical issues since birth, continued to struggle in public school.

Five years later, its standardized test scores show students tested in each of the last two years are, on average, making double-digit academic gains.

The Sentinel didn’t mention this in its description of TDR Learning Academy, a K-12 school in Orlando that enrolls about 90 students who use tax credit scholarships for low-income students, McKay scholarships for students with disabilities, and Gardiner scholarships for students with special needs such as autism and Down syndrome. Instead, in both its story and accompanying video, it portrayed the predominantly Hispanic school as a poster child for a regulatory accountability system it suggests is far too lax.

“These schools operate without state rules when it comes to teacher credentials, academics and facilities,” says the narrator in the Sentinel’s video. “TDR Academy in Orlando is one of them.”

The Senate will no longer hold confirmation hearings on prospective Education Secretary Betsy DeVos Wednesday, but another hearing will have at least as much potential to rock the world of public education.

The U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments in what could be a landmark special education case. And unlike confirmation hearings, marked by their predictable partisanship, the case has confounded the tribalism that typically marks America's education debate.

The nation's largest teachers union and the national charter school association have filed friend-of-the court briefs on the same side. The National Education Association is at odds with several associations of public-school administrators and districts.

Ironies abound. The school district in Douglas County, Colo. argues it shouldn't have to pay private school tuition for the family of a child with special needs. Yet the same school board is currently petitioning the high court to hear a separate case arguing its unique, district-created voucher program — which could help all students attend private schools at public expense — is constitutional.

At its core, Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District deals with bedrock questions about educators' obligation to help all children meet their potential.

It also highlights society’s evolution when it comes to educating children with special needs, and the ways the existing education system sometimes falls short of its ideals.

According to the Denver Post, Endrew's parents placed him in a private school that specialized in serving children with autism after he began to show serious behavior issues in the public school he attended.

The district, they argue, should reimburse them for tuition to fulfill its obligation to provide him with a Free Appropriate Public Education - a right spelled out in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, first passed in 1975. (more…)